Radulan Sahiron

Leader, operational commander

The Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) is an Islamist terrorist organization that seeks to establish an independent Islamic state in the southern Philippines. ASG is known for kidnapping innocents, including Westerners, for ransom, and beheading captives if their demands are not met.

July 30, 2022: A hundred former ASG members officially surrender to the Philippine government and return to their communities in Sulu.Roel Pareno, “100 former Abu Sayyaf members vow allegiance to gov’t,” Philippine Star, July 30, 2022, https://www.philstar.com/nation/2022/07/30/2199087/100-former-abu-sayyaf-members-vow-allegiance-govt.

The Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) is an Islamist terrorist organization that seeks to establish an independent Islamic state in the southern Philippines. ASG is known for kidnapping innocents, including Westerners, for ransom, and beheading captives if their demands are not met. ASG’s brutal decapitations date back to 2001, predating notorious beheadings carried out by al-Qaeda in Iraq and that group’s successor, ISIS.“Timeline: Hostage Crisis in the Philippines,” CNN, August 25, 2002, http://edition.cnn.com/2002/WORLD/asiapcf/southeast/06/07/phil.timeline.hostage/;

Garrett Atkinson, “Abu Sayyaf: The Father of the Swordsman: A Review of the Rise of Islamic Insurgency in the Southern Philippines,” American Security Project, March 2012, https://www.americansecurityproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Abu-Sayyaf-The-Father-of-the-Swordsman.pdf. ASG is also known for its relationship with al-Qaeda, which has become strained since the beginning of the U.S.-led Global War on Terror.Joe Penney, “The ‘War on Terror’ Rages in the Philippines,” Al Jazeera, October 5, 2011, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/inpictures/2011/10/2011104145947651645.html. The group is divided into two main factions: Radulan Sahiron, one of the United States’ most-wanted terrorists, leads the ASG faction based in Sulu, while a pro-ISIS faction was spearheaded by Basilan-based ASG leader Isnilon Hapilon before Hapilon’s death in October 2017.Carmela Fonbuena, “Abu Sayyaf top man Sahiron sends surrender feelers – military,” Rappler, April 19, 2017, http://www.rappler.com/nation/167207-abu-sayyaf-radullon-sahiron-surrender-feelers-military; Ted Regencia, “Marawi siege: Army kills Abu Sayyaf, Maute commanders,” Al Jazeera, October 16, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/10/marawi-siege-army-kills-abu-sayyaf-maute-commanders-171016072551985.html

In the summer of 2014, Hapilon and his followers pledged allegiance to ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. The pledge drew attention to ASG’s presence in the southern Philippines and its potential threat to Southeast Asia.Aurea Calica, “Islamic State Threatens Mindanao, Philippines Tells Asean,” Philippine Star (Manila), April 27, 2015. According to the Philippines’ Secretary of National Defense Delfin Lorenzana, ISIS made direct contact with Hapilon in December 2016, instructing him to find an area to establish a caliphate in MindanaoCarmela Fonbuena, “ISIS makes direct contact with Abu Sayyaf, wants caliphate in PH,” Rappler, January 26, 2017, http://www.rappler.com/nation/159568-isis-direct-contact-isnilon-hapilon. Afterward, Hapilon reportedly attempted to unite ISIS-supporting groups throughout the Philippines under his leadership.“Pro-ISIS Groups in Mindanao and Their Links to Indonesia and Malaysia,” Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, October 25, 2016, 2, http://file.understandingconflict.org/file/2016/10/IPAC_Report_33.pdf. In May 2017, the Philippine military launched an operation to target Hapilon in the city of Marawi. The operation devolved into a five-month-long armed conflict that displaced over 350,000 civilians, during which ASG and ISIS-linked militants laid siege to the city.Joseph Hincks, “The Battle for Marawi City,” Time, May 25, 2017, http://time.com/marawi-philippines-isis/; “Timeline: the Marawi crisis,” CNN Philippines, October 15, 2017, http://cnnphilippines.com/news/2017/05/24/marawi-crisis-timeline.html. The conflict ended shortly after Philippine troops killed Hapilon on October 16, 2017.Ted Regencia, “Marawi siege: Army kills Abu Sayyaf, Maute commanders,” Al Jazeera, October 16, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/10/marawi-siege-army-kills-abu-sayyaf-maute-commanders-171016072551985.html; Joseph Hincks, “The Leaders of the ISIS Assault on Marawi in the Philippines Have Been Killed,” Time, October 15, 2017, http://time.com/4983374/isis-philippines-killed-marawi-hapilon-maute/; Euan McKirdy and Joshua Berlinger, “Philippines’ Duterte declares liberation of Marawi from ISIS-affiliated militants,” CNN, October 17, 2017, http://www.cnn.com/2017/10/17/asia/duterte-marawi-liberation/index.html. In February 2019, the Associated Press reported that Hatib Hajan Sawadjaan, an ASG commander based in Jolo, became the new leader of ISIS in the Philippines. The U.S. Department of Defense believed Sawadjaan to be “acting emir,” but Philippine officials claimed that he was installed as head of ISIS in the Philippines the year prior.Jimmy Gomez, “Amid loss of leaders, unknown militant rises in Philippines,” Associated Press, February 21, 2019, https://www.apnews.com/730b6ee409364975817a82ad9f15d90c. In August 2020, the then Philippine army commanding general claimed that Sawadjaan had likely died following clashes with government forces in July 2020.Ellie Aben, “Philippine military says Abu Sayyaf leader still alive,” Arab News, July 11, 2020, https://www.arabnews.com/node/1702951/world; Jim Gomez, “Army chief: Militant leader likely killed in Philippines,” Associated Press, August 25, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/international-news-islamic-state-group-asia-pacific-d4595e2a569618d3f7abb3dd10aa30f7.

ASG has received funding and training from al-Qaeda and Jemaah Islamiyah (JI).“Country Report on Terrorism 2014,” U.S. Department of State, June 19, 2015, http://www.state.gov/j/ct/rls/crt/2014/239413.htm. ASG continues to provide sanctuary to foreign militant jihadists, such as JI fugitives.James Griffiths, “ISIS in Southeast Asia: Philippines battles growing threat,” CNN, May 29, 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2017/05/28/asia/isis-threat-southeast-asia/index.html. The group also maintains links with other Philippines-based extremist organizations, including the more violent splinter groups of both the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF).“Philippines-Mindanao Conflict,” Thomson Reuters Foundation, June 3, 2014, http://www.trust.org/spotlight/ -Mindanao-conflict/?tab=briefing.

ASG was founded by and named after Abdurajak Janjalani, who took the nom de guerre Abu Sayyaf, “Father of Swordsmen.” Janjalani previously participated in the MNLF, which, like ASG, sought to create an independent Islamic state in the MoroThe term “Moor”—“Moro” in Spanish—comes from the Muslim Arab and Berber peoples who invaded what became modern-day Spain and Portugal in the 700s. The Spanish came to refer to Muslims in North Africa by this term in the pre-colonial period. When Spanish colonists came to the Philippines in the 15th century, they again used “Moro” to describe darker-skinned, indigenous Filipino Muslims who attempted to push back against colonial expansion on their lands. While the term was once considered offensive, Filipino Muslims have taken ownership of it, calling themselves Moro and coining the term Bangsamoro (“bangsa” meaning state or nation) to describe their homeland. regions of Mindanao in the Philippines.Garrett Atkinson, “Abu Sayyaf: The Father of the Swordsman: A Review of the Rise of Islamic Insurgency in the Southern Philippines,” American Security Project, March 2012, https://www.americansecurityproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Abu-Sayyaf-The-Father-of-the-Swordsman.pdf. However, unlike ASG, the MNLF was willing to negotiate with the Philippine government (which it did, beginning in 1989) to achieve Moro autonomy.

Unhappy with the MNLF’s 1989 agreement with the Philippine government establishing the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM),“ARMM History and Organization,” GMA News, August 11, 2008, http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/112847/news/armm-history-and-organization. Janjalani and other radicals formally split from the MNLF in 1991 to form al Harakat al Islamiyya (the Islamic Movement),Octavio A. Dinampo, “Khadaffy Janjalani’s Last Interview,” Philippine Daily Inquirer (Makati City), January 22, 2007, http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/inquirerheadlines/nation/view/20070122-44761/A_last_ext. later known as ASG.Octavio A. Dinampo, “Khadaffy Janjalani’s Last Interview,” Philippine Daily Inquirer (Makati City), January 22, 2007, http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/inquirerheadlines/nation/view/20070122-44761/A_last_ext. They refused to settle for anything less than an independent Islamic state—and believed their only path to achieving that goal was through violent jihad.Zack Fellman, “Abu Sayyaf Group,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 2011, http://csis.org/files/publication/111128_Fellman_ASG_AQAMCaseStudy5.pdf.

In 1998, Philippine forces launched a counterterrorism raid on Basilan Island, killing ASG founder Abdurajak Janjalani in the ensuing shoot-out.“World: Asia-Pacific: Philippines Muslim Leader Killed,” BBC News, December 19, 1998, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/238499.stm. After his death, ASG splintered into two factions: one headed by Janjalani’s brother, Khadaffy Janjalani, on Basilan Island, and a second, headed by Ghalib Andang, a.k.a. Commander Robot, in the Sulu Archipelago.Zack Fellman, “Abu Sayyaf Group,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 2011, http://csis.org/files/publication/111128_Fellman_ASG_AQAMCaseStudy5.pdf.

During this period, ASG shifted its tactics from jihadist activities to terrorism conducted to meet the basic survival needs of the organization. Creating revenue through terrorism had been discussed internally among ASG’s leadership beginning in 1995, when Mohammed Jamal Khalifa, ASG’s main conduit to funding from al-Qaeda, was barred by the Philippine government from returning to the country. Zack Fellman, “Abu Sayyaf Group,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 2011, http://csis.org/files/publication/111128_Fellman_ASG_AQAMCaseStudy5.pdf. Andang advocated for the strategic use of kidnapping for ransom, believing that tactic would not only help bankroll ASG but raise the group’s profile and distinguish it from the more mainstream and increasingly less violent Moro organizations, such as the MILF and the MNLF.Garrett Atkinson, “Abu Sayyaf: The Father of the Swordsman: A Review of the Rise of Islamic Insurgency in the Southern Philippines,” American Security Project, March 2012, https://www.americansecurityproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Abu-Sayyaf-The-Father-of-the-Swordsman.pdf.

The Philippines received significant counterterrorism support from the United States in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, attacks. In 2002, the two countries launched Operation Enduring Freedom–Philippines, which set back ASG’s operations significantly. In March 2005, the counterterrorism force assassinated Commander Robot and later killed other potential rivals, leaving Khadaffy Janjalani positioned to assert control over all of ASG.“Commander Robot Among 23 Killed in Prison Siege,” Sydney Morning Herald, March 15, 2005, http://www.smh.com.au/news/World/Commander-Robot-among-23-killed-in-prison-siege/2005/03/15/1110649185247.html.

Khadaffy reoriented ASG toward committing ideologically motivated, large-scale terrorist attacks and to the goal of his late brother—establishing an Islamic state in the southern Philippines.Zack Fellman, “Abu Sayyaf Group,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 2011, http://csis.org/files/publication/111128_Fellman_ASG_AQAMCaseStudy5.pdf. Nonetheless, the group’s membership declined—another consequence of the Philippine-U.S. crackdown. The group’s numbers fell to 250 fighters in 2005 from a peak of 1,269 in 2000.Rommel C. Banlaoi, “The Abu Sayyaf Group: From Mere Banditry to Genuine Terrorism,” in Southeast Asian Affairs 2006, ed. Daljit Singh and Lorraine Carlos Salazar (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2006), 258. ASG is believed to be comprised of 300 to 400 armed militants as of February 2019.Associated Press, “5 militants linked to deadly church bombing surrender in the Philippines,” South China Morning Post, February 4, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/2185012/5-militants-linked-deadly-church-bombing-surrender.

Khadaffy Janjalani died in a shootout with Philippine forces on September 4, 2006, creating another power vacuum within the group. ASG then splintered along clan lines into smaller alliances, and the group returned to less ambitious terror activities. ASG factions in the Sulu archipelago continue to rely on kidnapping-for-ransom operations for its members’ survival and as a monetary incentive for recruitment.Zack Fellman, “Abu Sayyaf Group,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 2011, http://csis.org/files/publication/111128_Fellman_ASG_AQAMCaseStudy5.pdf. However, ASG, primarily the Basilan-based faction, has also engaged in increasingly large-scale terror plots that appear to be targeted toward the group’s ideological objectives.“Two Soldiers Killed in Abu Sayyaf Group Bomb Attack in Basilan,” GMA News, August 7, 2015, http://www.canadianinquirer.net/2015/06/25/abu-sayyaf-threatened-to-behead-two-coast-guard-officers/.

Throughout its existence, ASG has engaged in terrorism and guerilla warfare, targeting Catholics and Westerners, as well as locals of the villages ASG has infiltrated.“Currently Listed Entities,” Public Safety Canada, November 20, 2014, http://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/ntnl-scrt/cntr-trrrsm/lstd-ntts/crrnt-lstd-ntts-eng.aspx#2002. In many ways, ASG functions as an organized crime ring. Aside from pledging allegiance to ISIS in late July 2014, recent major group activities reflect members’ greed rather than extremist pursuits. One ASG analyst calls the group an “entrepreneur of violence.”Rommel C. Banlaoi, “The Sources of Abu Sayyaf’s Resilience in the Southern Philippines,” CTC Sentinel 3, no. 5 (May 2010), https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-sources-of-the-abu-sayyaf%E2%80%99s-resilience-in-the-southern-philippines. On the other hand, ASG is considered a resilient extremist group, willing to exploit opportunities for violence whether motivated by financial gain or Islamist ideology.Rommel C. Banlaoi, “The Sources of Abu Sayyaf’s Resilience in the Southern Philippines,” CTC Sentinel 3, no. 5 (May 2010), https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-sources-of-the-abu-sayyaf%E2%80%99s-resilience-in-the-southern-philippines.

ASG seeks to establish an independent Islamic state in western Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago, the predominately Muslim region in the south of the Philippines. ASG derives its ideology from the group’s eponymous founder, Abdurajak Janjalani, a.k.a. Abu Sayyaf.

In the early 1990s, Janjalani issued a public proclamation—the “Four Basic Truths”—which came to define ASG’s goals and ideology. The first “truth” emphasizes that ASG should serve as a bridge and balance between MNLF and MILF and should recognize the early leadership of both groups in the struggle for Moro liberation. Second, ASG’s ultimate goal is to establish in Mindanao an Islamic government whose “nature, meaning, emblem and objective” are synonymous with peace. However, the third truth asserts that the advocacy of war is necessary so long as oppression, injustice, capricious ambition, and arbitrary claims are imposed on Muslims. Lastly, ASG believes that “war disturbs peace only for the attainment of the true and real objective of humanity. That objective is the establishment of justice and righteousness for all under the law of the Koran and Sunnah.”Rommel C. Banlaoi, “The Abu Sayyaf Group: From Mere Banditry to Genuine Terrorism,” in Southeast Asian Affairs 2006, ed. Daljit Singh and Lorraine Carlos Salazar (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2006), 250.

Before Janjalani died in December 1998, he gave eight radical ideological discourses, called khutbahs. Janjalani asserted that Muslim scholars in the Philippines did not truly know the Quran, and therefore Filipino Muslims were not practicing pure Islam, unlike the Islam practiced widely in Indonesia and Malaysia. In the discourses, Janjalani revealed his knowledge of Wahhabism, which he learned while studying theology and Arabic in Libya, Syria, and Saudi Arabia. The Wahhabist brand of Sunni Islam is echoed in ASG’s early ideology, wherein members advocated for reforming Philippine Islamic practice, making it more pure and ultra-conservative.Rommel C. Banlaoi, “The Abu Sayyaf Group: From Mere Banditry to Genuine Terrorism,” in Southeast Asian Affairs 2006, ed. Daljit Singh and Lorraine Carlos Salazar (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2006), 251.

Since Janjalani’s death, ASG has lacked an ideological leader, stunting the group’s doctrinal development. The group’s preoccupation with illicit profits appears to have taken priority over ASG’s stated objective of creating an independent Islamic state in the southern Philippines.Thomas Koruth Samuel, “Radicalisation in Southeast Asia A Selected Case Study of Daesh in Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines,” Southeast Asia Regional Centre for Counter-Terrorism (SEARCCT), 2016, 86, https://www.unodc.org/documents/southeastasiaandpacific/Publications/2016/Radicalisation_SEA_2016.pdf. This is evidenced by the apparent lack of ideologically motivated recruitment efforts by ASG. Several analysts, such as Joseph Franco, research fellow at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, believe that the group is driven primarily by financial gain.Gabriel Dominguez, “Abu Sayyaf ‘Seeking Global Attention’ with Hostage Kill Threat,” Deutsche Welle, September 25, 2014, http://www.dw.com/en/abu-sayyaf-seeking-global-attention-with-hostage-kill-threat/a-17954921.

Other experts such as Sidney Jones of the Indonesia-based Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, however, believe that the rise of ISIS helped unify disparate Islamist militants in the Philippines under one ideological banner.Hannah Beech and Jason Gutierrez, “How ISIS Is Rising in the Philippines as It Dwindles in the Middle East,” New York Times, March 9, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/09/world/asia/isis-philippines-jolo.html; Sidney Jones, “How ISIS Got a Foothold in the Philippines,” New York Times, June 4, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/04/opinion/isis-philippines-rodrigo-duterte.html. Despite ISIS’s territorial losses in the Middle East, the terrorist group has inspired ASG fighters to help launch jihadist attacks. For example, on June 28, 2019, two suicide bombers killed five Philippine soldiers in an attack in Jolo, Sulu. ISIS claimed responsibility for the attack, and local authorities suspected that the ASG faction loyal to the global terrorist group were to blame. One of the suspected assailants was the first known Filipino militant to carry out a suicide bombing.Michael Hart, “Abu Sayyaf Is Bringing More of ISIS’ Brutal Tactics to the Philippines,” World Politics Review, July 22, 2019, https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/28054/abu-sayyaf-is-bringing-more-of-isis-brutal-tactics-to-the-philippines; Jim Gomez, “Philippines: 1st known Filipino suicide attacker identified,” Associated Press, July 2, 2019, https://www.apnews.com/2df091f681254512824864fe62ab4130.

ASG was a highly centralized organization under the leadership of ASG founder Abdurajak Janjalani. ASG’s hierarchy included a Majlis Shura Council and a separate military arm.Rommel C. Banlaoi, “The Abu Sayyaf Group: From Mere Banditry to Genuine Terrorism,” in Southeast Asian Affairs 2006, ed. Daljit Singh and Lorraine Carlos Salazar (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2006), 252. Since Janjalani’s death in 1998, however, ASG has increasingly descended into bands of armed groups scattered throughout the southern Mindanao region.Zack Fellman, “Abu Sayyaf Group,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 2011, http://csis.org/files/publication/111128_Fellman_ASG_AQAMCaseStudy5.pdf.

Analysts such as Rommel Banlaoi of the Philippine Institute for Peace, Violence, and Terrorism Research believe that this decentralized structure has enabled ASG to stay resilient, allowing the group to form partnerships with other Islamist cells that operate in the southern Philippines.“Pro-ISIS Groups in Mindanao and Their Links to Indonesia and Malaysia,” Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (Indonesia), October 25, 2016, 1, http://file.understandingconflict.org/file/2016/10/IPAC_Report_33.pdf.; Rommel C. Banlaoi, “The Sources of Abu Sayyaf’s Resilience in the Southern Philippines,” CTC Sentinel 3, no. 5 (May 2010), https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-sources-of-the-abu-sayyaf%E2%80%99s-resilience-in-the-southern-philippines. ASG has also been able to build its finances by tapping into an existing network of narco-traffickers who reportedly help propel ASG’s illicit drug activities, including running marijuana rings.“Troops in Clash with Abu Sayyaf were on Recon Mission, Says AFP Spokesman,” GMA News, November 17, 2015, http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/388449/news/regions/troops-in-clash-with-abu-sayyaf-were-on-recon-mission-says-afp-spokesman. ASG’s network also pressures local populations to allow ASG to operate amongst them.Rommel C. Banlaoi, “The Sources of Abu Sayyaf’s Resilience in the Southern Philippines,” CTC Sentinel 3, no. 5 (May 2010), https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-sources-of-the-abu-sayyaf%E2%80%99s-resilience-in-the-southern-philippines.

Two major factions have been operating under the ASG banner in recent years: the Sulu-based faction headed by Radulan Sahiron and an ISIS-supporting faction, historically based in Basilan, led by Isnilon Hapilon before his death in October 2017.Ted Regencia, “Marawi siege: Army kills Abu Sayyaf, Maute commanders,” Al Jazeera, October 16, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/10/marawi-siege-army-kills-abu-sayyaf-maute-commanders-171016072551985.html; Joseph Hincks, “The Leaders of the ISIS Assault on Marawi in the Philippines Have Been Killed,” Time, October 15, 2017, http://time.com/4983374/isis-philippines-killed-marawi-hapilon-maute/.

Sulu-Based FactionRadulan Sahiron, one of the United States’ most-wanted terrorists, leads the ASG faction based in Sulu.Carmela Fonbuena, “Abu Sayyaf top man Sahiron sends surrender feelers – military,” Rappler, April 19, 2017, http://www.rappler.com/nation/167207-abu-sayyaf-radullon-sahiron-surrender-feelers-military Sahiron was named the leader of ASG following Khadaffy Janjalani’s death in 2005, though ASG members who support ISIS consider Hapilon to be ASG’s leader.“Pro-ISIS Groups in Mindanao and Their Links to Indonesia and Malaysia,” Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (Indonesia), October 25, 2016, 2, http://file.understandingconflict.org/file/2016/10/IPAC_Report_33.pdf. Sahiron and the Sulu-based faction have reportedly rejected ISIS and remain committed to the realization of a local, regional caliphate.Carmela Fonbuena, “Abu Sayyaf top man Sahiron sends surrender feelers – military,” Rappler, April 19, 2017, http://www.rappler.com/nation/167207-abu-sayyaf-radullon-sahiron-surrender-feelers-military. However, there were reports of an alignment between the groups when ISIS’s Amaq News Agency claimed attacks carried out by the Sulu-based faction in May and June of 2017.Michael Quinones, “More dangerous union: Abu Sayyaf Sulu and ISIS East Asia finally align,” Rappler, July 17, 2017. https://www.rappler.com/nation/175812-trac-abu-sayyaf-isis-alignment.

ASG’s Sulu-based faction is primarily responsible for the series of high-profile ASG kidnappings, beheadings, and piracy attacks in Mindanao.Carmela Fonbuena, “Abu Sayyaf top man Sahiron sends surrender feelers – military,” Rappler, April 19, 2017, http://www.rappler.com/nation/167207-abu-sayyaf-radullon-sahiron-surrender-feelers-military. According to the Philippine military, Sahiron signaled in April 2017 that he may be willing to negotiate for his surrender following a wave of sustained military offenses in Sulu.Manny Mogato, “Abu Sayyaf with US bounty reportedly wants to surrender,” ABS-CBN News, April 20, 2017, http://news.abs-cbn.com/news/04/20/17/abu-sayyaf-with-us-bounty-reportedly-wants-to-surrender.

On March 6, 2020, a group of ASG militants surrendered in Sulu, and on March 9, another group who were also followers of Hatib Hajan Sawadjaan, a local leader of ISIS, surrendered to the Philippine Army. Overall, 10 militants surrendered to army forces due to the lack of support from residents due to the repercussions of on-going counterterrorism operations in the area.Roel Pareno, “10 Abu Sayyaf bandits surrender in Sulu,” Philippine Star, March 15, 2020, https://www.philstar.com/nation/2020/03/15/2000888/10-abu-sayyaf-bandits-surrender-sulu.

Sawadjaan’s nephew, Mudzrimar “Mundi” Sawadjaan, is also a unit sub-leader and bombmaker of ASG in Sulu. He is the suspected mastermind of the August 2020 twin blasts in Jolo, Sulu, which killed at least 14 people and wounded dozens of others. According to a military spokesman, Mundi Sawadjaan controls a group of about 40 fighters as of September 2020.Rambo Talabong, “Mundi Sawadjaan behind Jolo twin bombings, military says,” Rappler, August 27, 2020, https://www.rappler.com/nation/military-report-person-behind-jolo-bombings; “Military seizes alleged hideout of Abu Sayyaf's Mundi Sawadjaan in Sulu,” ABS-CBN News, September 22, 2020, https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/09/22/20/military-seizes-alleged-hideout-of-abu-sayyafs-mundi-sawadjaan-in-sulu.

ISIS and the Basilan-Based FactionIn February 2019, the Associated Press reported that Hatib Hajan Sawadjaan, an ASG commander based on Jolo, became the new leader of ISIS in the Philippines. The U.S. Department of Defense believed Sawadjaan to be “acting emir,” but Philippine officials claimed that he was installed as head of ISIS in the Philippines in 2018. Sawadjaan had been active in the Sulu-based faction under Sahiron, but he reportedly split from Sahiron over the latter’s disinterest in integrating foreign militants.Jimmy Gomez, “Amid loss of leaders, unknown militant rises in Philippines,” Associated Press, February 21, 2019, https://www.apnews.com/730b6ee409364975817a82ad9f15d90c. In 2019, Sawadjaan controlled between five or six sub-groups within ASG, consisting of a total of approximately 100 fighters.Associated Press, “5 militants linked to deadly church bombing surrender in the Philippines,” South China Morning Post, February 4, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/2185012/5-militants-linked-deadly-church-bombing-surrender. It was reported that pro-ISIS groups in the Philippines convened a meeting in May or June 2019 and officially selected Sawadjaan as their leader.“The Philippines: Militancy and the New Bangsamoro,” International Crisis Group, June 27, 2019, https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/philippines/301-philippines-militancy-and-new-bangsamoro. He was believed to have harbored foreign terrorists and Islamist extremists, including the Indonesian couple that carried out the January 2019 Cathedral bombing in Jolo, Sulu.Jimmy Gomez, “Amid loss of leaders, unknown militant rises in Philippines,” Associated Press, February 21, 2019, https://www.apnews.com/730b6ee409364975817a82ad9f15d90c. The attack was orchestrated by a cell under Sawadjaan, known as the Ajang-Ajang.Michael Hart, “Abu Sayyaf Is Bringing More of ISIS’ Brutal Tactics to the Philippines,” World Politics Review, July 22, 2019, https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/28054/abu-sayyaf-is-bringing-more-of-isis-brutal-tactics-to-the-philippines. Sawadjaan was also linked to a number of high-profile kidnappings and executions, including the beheadings of two Canadians in 2016.Associated Press, “5 militants linked to deadly church bombing surrender in the Philippines,” South China Morning Post, February 4, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/2185012/5-militants-linked-deadly-church-bombing-surrender. In July 2020, local Philippine media reported that Sawadjaan had died days after he was injured in a clash with government forces, though the military later claimed he survived. In August 2020, a military official claimed Sawadjaan was likely killed, but troops were working to recover his remains to confirm his death.Ellie Aben, “Philippine military says Abu Sayyaf leader still alive,” Arab News, July 11, 2020, https://www.arabnews.com/node/1702951/world; Jim Gomez, “Army chief: Militant leader likely killed in Philippines,” Associated Press, August 25, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/international-news-islamic-state-group-asia-pacific-d4595e2a569618d3f7abb3dd10aa30f7.

Isnilon Totoni Hapilon, the former leader of ISIS in Southeast Asia, led the ASG faction that has historically been based in Basilan in southern Mindanao before his death on October 16, 2017. According to the Philippine military, ISIS leaders in Syria made direct contact with Hapilon and called on him to stake out possible areas for a caliphate in Mindanao. Following ISIS orders, Hapilon and other Basilan-based members reportedly moved to central Mindanao in an attempt to unite with other ISIS-supporting terrorist groups in the country.Carmela Fonbuena, “ISIS makes direct contact with Abu Sayyaf, wants caliphate in PH,” Rappler, January 26, 2017, http://www.rappler.com/nation/159568-isis-direct-contact-isnilon-hapilon; “Pro-ISIS Groups in Mindanao and Their Links to Indonesia and Malaysia,” Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (Indonesia), October 25, 2016, 2, http://file.understandingconflict.org/file/2016/10/IPAC_Report_33.pdf.

In July 2014, Hapilon and his militants pledged allegiance to ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.Maria A. Ressa, “Senior Abu Sayyaf leader swears oath to ISIS.” Rappler, August 4, 2015, http://www.rappler.com/nation/65199-abu-sayyaf-leader-oath-isis. The Basilan-based group under Hapilon effectively ceased most of its kidnapping activities after the pledge.“Protecting the Sulu-Sulawesi Seas from Abu Sayyaf Attacks,” Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, January 9, 2019, 10, http://file.understandingconflict.org/file/2019/01/IPAC_Report_53_Sulu.pdf. In January 2016, Hapilon’s group, using their alternative name Harakatul Islamiyah (Islamic Movement), again pledged allegiance to ISIS in a video posted online and named Hapilon the leader of ASG.Moh Saaduddin, “Abu Sayyaf rebels pledge allegiance to ISIS,” Manila Times, January 11, 2016, http://www.manilatimes.net/breaking_news/abu-sayyaf-rebels-pledge-allegiance-to-isis/. Hapilon and his faction received international attention in May 2017 when they were the target of a Philippine military raid in Marawi City that devolved into a violent siege and resulted in President Rodrigo Duterte calling for martial law in Mindanao. The raid was originally carried out to target Hapilon, who was allegedly in Marawi to meet with the Maute Group, an ISIS-linked group based in the area.Greanne Trisha Mendoza, “LOOK: Marawi City jail, Dansalan College on fire,” ABS-CBN News, May 23, 2017, http://news.abs-cbn.com/news/05/23/17/duterte-wont-cut-short-russia-trip-amid-marawi-siege; Associated Press, “Philippine troops try to retake city stormed by ISIS allies,” CBS News, May 25, 2017, http://www.cbsnews.com/news/philippines-isis-abu-sayyaf-maute-marawi-rodrigo-duterte-emergency/. Hapilon was killed in a military operation in the city of Marawi on October 16, 2017.Ted Regencia, “Marawi siege: Army kills Abu Sayyaf, Maute commanders,” Al Jazeera, October 16, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/10/marawi-siege-army-kills-abu-sayyaf-maute-commanders-171016072551985.html; Joseph Hincks, “The Leaders of the ISIS Assault on Marawi in the Philippines Have Been Killed,” Time, October 15, 2017, http://time.com/4983374/isis-philippines-killed-marawi-hapilon-maute/. The following day, Duterte announced the liberation of Marawi from ISIS-affiliated militants.Euan McKirdy and Joshua Berlinger, “Philippines’ Duterte declares liberation of Marawi from ISIS-affiliated militants,” CNN, October 17, 2017, http://www.cnn.com/2017/10/17/asia/duterte-marawi-liberation/index.html.

Following Hapilon’s death, Furuji Indama was believed to have taken charge of the Basilan-based ASG faction.“Protecting the Sulu-Sulawesi Seas from Abu Sayyaf Attacks,” Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, January 9, 2019, 3, http://file.understandingconflict.org/file/2019/01/IPAC_Report_53_Sulu.pdf. It is not known whether Indama pledged allegiance to ISIS or what connection he has with militants who supported Hapilon’s shift to ISIS.“The Philippines: Militancy and the New Bangsamoro,” International Crisis Group, June 27, 2019, https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/philippines/301-philippines-militancy-and-new-bangsamoro. In 2019, Philippine police arrested a number of ASG members operating under Indama, including one suspect linked to a 2015 bombing at a bus terminal that killed an 11-year-old girl.Leizel Lacastesantos, “Alleged Abu member linked to 2017 Zamboanga bus station bombing arrested,” ABS-CBN News, July 24, 2019, https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/07/24/19/alleged-abu-member-linked-to-2015-zamboanga-bus-station-bombing-arrested; “The Philippines: Militancy and the New Bangsamoro,” International Crisis Group, June 27, 2019, https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/philippines/301-philippines-militancy-and-new-bangsamoro. In October 2020, the Philippine military announced that it believed Indama had been fatally wounded during a September 2020 clash with the armed forces. The military is still working to locate his remains in order to confirm his death.“Military believes Abu Sayyaf subleader Furuji Indama is dead,” Rappler, October 30, 2020, https://www.rappler.com/nation/military-believes-abu-sayyaf-subleader-furuji-indama-dead.

ASG’s main funding sources are its kidnapping-for-ransom and extortion enterprises. ASG primarily targets Westerners and other wealthy foreign nationals for kidnapping. The group has also been known to target local politicians, business people, and civilians.“Abu Sayyaf Group,” Australian National Security, accessed June 26, 2015, http://www.nationalsecurity.gov.au/Listedterroristorganisations/Pages/AbuSayyafGroup.aspx. In addition to its dependence on ransom, ASG engages in extortion, collecting so-called taxes from businesses and locals within ASG’s areas of influence. The group also offers ‘protection’ to certain local moneymaking endeavors, reportedly including marijuana farms in the Sulu Archipelago.Gabriel Dominguez, “Abu Sayyaf ‘Seeking Global Attention’ with Hostage Kill Threat,” Deutsche Welle, September 25, 2014, http://www.dw.com/en/abu-sayyaf-seeking-global-attention-with-hostage-kill-threat/a-17954921. In February 2018, the Department of Public Works and Highways in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (DWPH-ARMM) reported that ASG threatened to delay the implementation of vital infrastructure projects in Basilan if the militants were not paid “protection money” of at least 200,000 Philippine pesos.Nonoy E. Lacson, “ASG extortion activities worsen in Basilan,” Manila Bulletin, February 5, 2018, https://news.mb.com.ph/2018/02/04/asg-extortion-activities-worsen-in-basilan/.

In addition to violent and criminal activity, ASG has reportedly received funding and logistical support through a network of jihadist groups, including Hezbollah, Jamaat-e-Islami, Hizbul-Mujahideen in Pakistan, Hizb-i-Islami Gulbuddin in Afghanistan, al Gama’a al-Islamiyya in Egypt, International Harakatu’l al-Islamia in Libya, and the Islamic Liberation Front in Algeria.Rommel C. Banlaoi, “The Abu Sayyaf Group: From Mere Banditry to Genuine Terrorism,” in Southeast Asian Affairs 2006, ed. Daljit Singh and Lorraine Carlos Salazar (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2006), 249. ASG has also received funds from Jemaah Islamiyah (JI). In exchange, ASG continues to harbor JI militants who provide in-kind assistance to the group, in the form of military and bomb-making training. “Country Report on Terrorism 2014,” U.S. Department of State, June 19, 2015, 332, http://www.state.gov/j/ct/rls/crt/2014/.

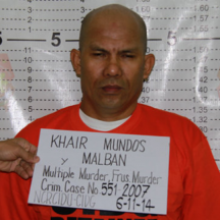

ASG received a majority of its seed funding from al-Qaeda. The most notorious ASG financier was one of Osama bin Laden’s brothers-in-law, Mohammed Jamal Khalifa. From the late 1980s to the early 1990s, Khalifa established a Philippine branch of the Saudi-based International Islamic Relief Organization (IIRO), an illicit charity organization used to channel funds to ASG.“Treasury Designated Director, Branches of Charity Bankrolling Al Qaida Network,” U.S. Department of Treasury, August 3, 2006, http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/hp45.aspx. ASG’s leadership used the funds to pay for training its members and building up its arms.“Narrative Summaries of Reasons for Listing – Qde.001 Abu Sayyaf Group,” United Nations Security Council Committee pursuant to resolution 1267 (1999) and 1989 (2011) concerning Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities, February 3, 2015, http://www.un.org/sc/committees/1267/NSQDe001E.shtml. In the mid-1990s, Mahmud Abd al-Jalil Afif ran the IIRO Philippines, using the organization to funnel money to terrorist groups, and was a major ASG supporter. “Treasury Designated Director, Branches of Charity Bankrolling Al Qaida Network,” U.S. Department of Treasury, August 3, 2006, http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/hp45.aspx. In June 2014, ASG senior leader Khair Mundos was arrested after a seven-year manhunt, having been designated as a U.S. most-wanted terrorist. Mundos confessed to transferring funds from al-Qaeda to former ASG leader Khadaffy Janjalani. The funds were earmarked for use in bombings and other criminal acts throughout Mindanao.David Stout, “One of the U.S.’s ‘Most Wanted’ Terrorists Is Arrested in the Philippines,” Time, June 11, 2014, http://time.com/2856423/terrorist-most-wanted-khair-mundos-philippines-abu-sayyaf/. In 1995, Khalifa was refused re-entry into the Philippines for his association with Ramzi Yousef, who plotted the 1993 World Trade Center attack and the Bojinka Plot. Consequently, ASG lost a major financial pipeline and connection to al-Qaeda Central.Zack Fellman, “Abu Sayyaf Group,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 2011, http://csis.org/files/publication/111128_Fellman_ASG_AQAMCaseStudy5.pdf.

ASG has also received funding through remittances from Filipinos working overseas and from other extremists in the Middle East.“Country Report on Terrorism 2014,” U.S. Department of State, June 19, 2015, 332, http://www.state.gov/j/ct/rls/crt/2014/. Philippine officials maintain that funds secured through these channels are miniscule compared to ASG’s other sources of funding. Authorities maintain that this pipeline may be unintentional, as money sent to Filipino families may be intercepted by ASG operatives via wire transfer agencies and redirected to ASG’s coffers.“Military Clueless on OFWs Funding Abu Sayyaf,” ABS-CBN News, November 19, 2010, http://www.abs-cbnnews.com/global-filipino/11/18/10/military-clueless-ofws-funding-abu-sayyaf. Remittances from Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) are an integral component of the Philippine economy, accounting for nearly 10 percent of the country’s GDP.“Personal remittances, received (% of GDP),” World Bank, accessed January 25, 2015, http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS. OFWs working in Western or Middle Eastern countries send money through a wire transfer agency, such as MoneyGram or Western Union and their agents in the Philippines. Some OFWs are unaware that their money is channeled to the extremist group, while other OFWs may be sympathetic to ASG’s cause or are relatives or friends of the militants.Caren Gwen Mayola, “Crime-Terror Nexus in Terrorist Financing – Philippines: The Abu Sayyaf Group,” Thomson Reuters, June 23, 2014, https://risk.thomsonreuters.com/sites/default/files/GRC00946.pdf.

Following the siege of Marawi in 2017, the Philippine military chief revealed that ISIS had funneled a “couple of million dollars” to Hapilon’s faction. The terrorist organization reportedly sent at least $1.5 million to finance the siege, which began in May 2017 and killed more than 1,100 people and displaced approximately 400,000 residents.Associated Press, “AP Exclusive: Video shows militants in Philippine siege plot,” Philippine Daily Inquirer (Makati City), June 6, 2017, https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/903146/ap-exclusive-video-shows-militants-in-philippine-siege-plot; Jim Gomez, “AP Interview: Philippine military chief says IS funded siege,” Associated Press, October 24, 2017, https://www.apnews.com/0dde0525561f424d860d445fa691ec5e.

Traditionally, ASG draws members from clan and family groups.“Abu Sayyaf Group,” Australian National Security, accessed June 26, 2015, http://www.nationalsecurity.gov.au/Listedterroristorganisations/Pages/AbuSayyafGroup.aspx. According to the Australian government, most of ASG’s new recruits (as of 2013) are young Muslims from the impoverished southernmost islands of the Philippines, primarily the main Mindanao region and the Sulu Archipelago. At times, the group has also absorbed foreign fighters into its ranks, including IndonesianZachary Abuza, “The Demise of the Abu Sayyaf Group in the Southern Philippines,” CTC Sentinel 1, no. 7 (June 2008), https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-demise-of-the-abu-sayyaf-group-in-the-southern-philippines. and Malaysian“Philippines Hunts Malaysian Suspect with Abu Sayyaf Militants,” Straits Times (Singapore), May 16, 2015, http://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/philippines-hunts-malaysian-suspect-with-abu-sayyaf-militants. jihadists.

According to Australian intelligence, ASG works to recruit members so that it maintains a base of at least 400 fighters. Despite these reported aspirations, ASG membership appears to have fluctuated significantly—increasing in correlation with the success of its terror operations, and then decreasing as pressure mounts from the Philippine military. According to Filipino security analyst Rommel C. Banlaoi, ASG’s illicit operations have enhanced the group’s resources and reputation, facilitating recruitment.Rommel C. Banlaoi, “The Sources of Abu Sayyaf’s Resilience in the Southern Philippines,” CTC Sentinel 3, no. 5 (May 2010), https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-sources-of-the-abu-sayyaf%E2%80%99s-resilience-in-the-southern-philippines.

Many of the areas in the southern Philippines where ASG is most active—the Sulu Archipelago, Basilan, and Tawi-Tawi—lack economic opportunities and infrastructure. Locals rely on subsistence fishing and struggle with difficult agricultural conditions.Gabriel Dominguez, “Abu Sayyaf ‘Seeking Global Attention’ with Hostage Kill Threat,” Deutsche Welle, September 25, 2014, http://www.dw.com/en/abu-sayyaf-seeking-global-attention-with-hostage-kill-threat/a-17954921. Recruits to ASG appear to be primarily motivated by the promise of wealth and status rather than ideological fulfillment. This is unsurprising, given the group’s vacillation between jihadist-style, ideologically driven operations and criminal activity for financial gain.John Rollins and Liana Sun Wyler, “Terrorism and Transnational Crime: Foreign Policy Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, June 11, 2012, https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/terror/R41004.pdf. For example, in the Sulu Archipelago, Basilan, and Tawi-Tawi, poor Muslim parents volunteer their sons to join ASG in exchange for monthly food supplies and financial support amounting to a few hundred dollars.Rommel C. Banlaoi, “The Sources of Abu Sayyaf’s Resilience in the Southern Philippines,” CTC Sentinel 3, no. 5 (May 2010), https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-sources-of-the-abu-sayyaf%E2%80%99s-resilience-in-the-southern-philippines.

In some cases, youths joined ASG as a status symbol, setting themselves apart from their peers who sought criminal activity through ordinary street gangs. Other recruitment motivations have included ASG’s marijuana production and openness to use of the drug, revenge for family members killed by the Philippine police or military, or clan conflicts that abound in Mindanao.Rommel C. Banlaoi, “The Sources of Abu Sayyaf’s Resilience in the Southern Philippines,” CTC Sentinel 3, no. 5 (May 2010), https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-sources-of-the-abu-sayyaf%E2%80%99s-resilience-in-the-southern-philippines. ASG exploits youth in these underserved and marginalized areas, seducing them with the promise of wealth or notoriety. More recently, the group has used its pledge to ISIS as a propaganda tactic to bring in new recruits.Gabriel Dominguez, “Abu Sayyaf ‘Seeking Global Attention’ with Hostage Kill Threat,” Deutsche Welle, September 25, 2014, http://www.dw.com/en/abu-sayyaf-seeking-global-attention-with-hostage-kill-threat/a-17954921.

During the Marawi siege that began in May 2017, ASG members and other militants documented their victories—real or perceived—and clashes with Philippine government forces on ISIS social media accounts.Natashya Gutierrez, “How pro-ISIS fighters recruited Filipino youth for Marawi siege,” Rappler, July 22, 2017, https://www.rappler.com/world/regions/asia-pacific/176302-muslim-youth-recruitment-marawi. According to a report from the Indonesia-based Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, Filipino fighters who posted on ISIS-supporting Telegram channels were able to create an international constituency for the Marawi jihad. They used social media to perpetuate the narrative that the Philippine government was to blame because of its oppression of Muslims in Mindanao and, during the siege, for destruction of the city.“Marawi, The “East Asia Wilayah” and Indonesia,” Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, July 21, 2017, http://file.understandingconflict.org/file/2017/07/IPAC_Report_38.pdf.

Both al-Qaeda and JI have trained ASG members in guerrilla warfare, military operations, and bomb making.“Narrative Summaries of Reasons for Listing – Qde.001 Abu Sayyaf Group,” Security Council Committee pursuant to resolution 1267 (1999) and 1989 (2011) concerning Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities, February 3, 2015, http://www.un.org/sc/committees/1267/NSQDe001E.shtml. Before the 2001 war in Afghanistan, ASG members occasionally trained there with al-Qaeda. After the post-9/11 crackdown on al-Qaeda and its affiliates, the cooperation between the larger group and ASG has been limited. However, several ASG members who trained with al-Qaeda are still active. The U.S. National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) claims that ASG members receive continued operational guidance from al-Qaeda affiliates who are in hiding or visiting the Philippines. “Abu Sayyaf Group,” National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, accessed January 25, 2016, http://www.start.umd.edu/tops/terrorist_organization_profile.asp?id=204.

ASG has a long history of receiving training in bomb-making and weapons from foreign terrorists. Ramzi Yousef—perpetrator of the 1995 World Trade Center bombing—trained a small ASG cadre in bomb-making, having experimented with various bombs and explosives in an apartment in the Philippines.Zack Fellman, “Abu Sayyaf Group,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 2011, http://csis.org/files/publication/111128_Fellman_ASG_AQAMCaseStudy5.pdf. Two well-known Indonesian JI members—Dulmatin and Umar Patek, the masterminds behind the deadly 2002 Bali bombings—traveled to the Philippines to train ASG militants. Philippine intelligence identified the two as key trainers on the manufacture and use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs).Rommel C. Banlaoi, “The Sources of Abu Sayyaf’s Resilience in the Southern Philippines,” CTC Sentinel 3, no. 5 (May 2010), https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-sources-of-the-abu-sayyaf%E2%80%99s-resilience-in-the-southern-philippines.

ASG has become adept at maritime terror attacks, as evidenced by its targeting of ferries and various sea vehicles carrying tourists. Almost all members of ASG have some knowledge of the maritime domain, as descendants from a long Moro tradition of seafaring and subsistence fishing. To further its kidnap-for-ransom agenda, ASG trains its members to overtake and attack boats, ships, and barges.Rommel C. Banlaoi, “The Abu Sayyaf Group: From Mere Banditry to Genuine Terrorism,” in Southeast Asian Affairs 2006, ed. Daljit Singh and Lorraine Carlos Salazar (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2006), 254.

Leader, operational commander

Leader of Basilan faction and alleged ISIS leader in Southeast Asia (deceased)

Religious leader

Leader of Basilan-based faction (deceased)

Co-commander of the Basilan faction

Leader for Islamic propagation and indoctrination

Fundraiser, bomb maker, arrested

Spokesperson, senior leader, confirmed dead

Founder and former emir, confirmed dead

Former emir and senior leader, confirmed dead

Emir (leader) of ISIS in the Philippines (reportedly deceased)

Sulu-based commander of Abu Sayyaf Group (reportedly deceased)

Unit sub-leader, bombmaker

ASG’s terror attacks can be categorized as either ideologically charged violent jihad or profit-seeking terror activities. The first group includes large-scale terror attacks targeting strategic assets, such as bombing Philippine military bases or law enforcement facilities. This group also includes attacks, kidnappings, and beheadings of Western targets such as missionaries and tourist destinations. The second type of terror activity, which includes kidnapping for ransom, has become ASG’s modus operandi. These smaller-scale attacks are not necessarily ideologically motivated but are instead used to finance the group, along with extortion from businesses, forced taxation of locals, and kidnap-for-ransom operations.

ASG has enjoyed a historically symbiotic relationship with al-Qaeda, receiving funding and training from al-Qaeda and its network in return for a safe haven and operational support for al-Qaeda operatives. During 1991 and 1992, Ramzi Yousef—perpetrator of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing—traveled in and out of the Philippines with Abdurajak Janjalani.Zack Fellman, “Abu Sayyaf Group,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 2011, http://csis.org/files/publication/111128_Fellman_ASG_AQAMCaseStudy5.pdf. Yousef was able to return to the Philippines after the 1993 bombing unscathed and began planning what was to be known as the Bojinka plot with Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM).Zack Fellman, “Abu Sayyaf Group,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 2011, http://csis.org/files/publication/111128_Fellman_ASG_AQAMCaseStudy5.pdf. The duo planned to bomb at least 12 Western airliners traveling over the Pacific Ocean. ASG provided operational support to the two.Zack Fellman, “Abu Sayyaf Group,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 2011, http://csis.org/files/publication/111128_Fellman_ASG_AQAMCaseStudy5.pdf.

Ultimately, the Bojinka plot failed due in part to a chemical fire that Yousef started in his kitchen in Manila while attempting to create a liquid explosive device. The fire attracted the Philippine police, who in turn shared recovered files with the United States.Aurel Croissant and Daniel Barlow, “Government Responses in Southeast Asia,” Terrorism Financing and State Responses: A Comparative Perspective (Stanford: Stanford University Press), 212. According to the 9/11 Commission Report, KSM first conceived of using aircraft as weapons during this time, later inspiring him to reemploy this strategy for the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, The 9/11 Commission Report: Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2004), 149, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf.

Leader of ASG’s Basilan-based faction, Isnilon Hapilon, flanked by a group of guerrillas, pledged allegiance to ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in the summer of 2014.Michelle FlorCruz, “Philippine Terror Group Abu Sayyaf May Be Using ISIS Link for Own Agenda,” International Business Times, September 25, 2014, http://www.ibtimes.com/philippine-terror-group-abu-sayyaf-may-be-using-isis-link-own-agenda-1695156. Though ISIS has not declared a province or wilayat in the region as of February 2017, the group reportedly endorsed Hapilon as emir for Southeast Asia in June.“Pro-ISIS Groups in Mindanao and Their Links to Indonesia and Malaysia,” Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (Indonesia), October 25, 2016, 1, http://file.understandingconflict.org/file/2016/10/IPAC_Report_33.pdf. In a June 2016 video, alleged Indonesian, Malaysian and Filipino fighters acknowledged Hapilon as the head of ISIS in Southeast Asia.“ISIS recruits in SE Asia is a rising threat despite weak attacks,” Associated Press, July 14, 2016, http://english.alarabiya.net/en/perspective/features/2016/07/14/ISIS-recruits-in-SE-Asia-a-rising-threat-despite-weak-attacks.html. According to the Philippines’ Secretary of National Defense, ISIS made direct contact with Hapilon in December 2016, instructing him to find an area to establish a caliphate in Mindanao.Carmela Fonbuena, “ISIS makes direct contact with Abu Sayyaf, wants caliphate in PH,” Rappler, January 26, 2017, http://www.rappler.com/nation/159568-isis-direct-contact-isnilon-hapilon.

The Philippine government leaked a document from August 2014 that tells of close to 200 Filipinos who may have fought with ISIS. However, there were no domestic plots related to ISIS reported by the government at that time.Michelle FlorCruz, “Philippine Terror Group Abu Sayyaf May Be Using ISIS Link for Own Agenda,” International Business Times, September 25, 2014, http://www.ibtimes.com/philippine-terror-group-abu-sayyaf-may-be-using-isis-link-own-agenda-1695156. In a report from a major Philippine news channel, the mayor of a city on Basilan Island claimed that ISIS had been present, proselytizing in religious centers, for a few months. In the same news report, there were some local officials who claimed ISIS flags have been present since 2006. However, officials from the Armed Forces of the Philippines are skeptical that this is the case.“ISIS Joins Forces with Abu Sayyaf, BIFF in Basilan,” ABS-CBN News, September 24, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8iRroDkaohw.

On September 19, 2014, photos emerged from the city of Marawi in ASG’s stronghold of southern Mindanao, showing ISIS flags and members with their faces covered in front of a mosque. The chief of police in Marawi has confirmed their presence, asserting that if they remained peaceful and actions were “within the law,” they would not be arrested.“Bandila ng ISIS, Namataan sa Marawi,” ABS-CBN News, September 24, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ytpR5LLa2eE. In May 2017, an ISIS-linked organization operating in Marawi, the Maute Group, became violent following a Philippine military raid on an apartment building reportedly serving as Hapilon’s hideout. According to Philippine authorities, Hapilon was in Marawi to join forces with the Maute Group. The ISIS-linked militants laid siege to the city, burning several structures as Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte called for martial law on the entire island of Mindanao.Greanne Trisha Mendoza, “LOOK: Marawi City jail, Dansalan College on fire,” ABS-CBN News, May 23, 2017, http://news.abs-cbn.com/news/05/23/17/duterte-wont-cut-short-russia-trip-amid-marawi-siege; Associated Press, “Philippine troops try to retake city stormed by ISIS allies,” CBS News, May 25, 2017, http://www.cbsnews.com/news/philippines-isis-abu-sayyaf-maute-marawi-rodrigo-duterte-emergency/. Hapilon and the commander of the Maute group were killed in an operation on October 16, 2017.Ted Regencia, “Marawi siege: Army kills Abu Sayyaf, Maute commanders,” Al Jazeera, October 16, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/10/marawi-siege-army-kills-abu-sayyaf-maute-commanders-171016072551985.html; Joseph Hincks, “The Leaders of the ISIS Assault on Marawi in the Philippines Have Been Killed,” Time, October 15, 2017, http://time.com/4983374/isis-philippines-killed-marawi-hapilon-maute/.

ASG provided a special training camp to JI militants in its stronghold of southern Mindanao. JI militants intermingled with ASG during this time, training together on subjects such as bomb making.“Marwan Alive Has Serious Implications: Trillanes,” ABS-CBN News, August 7, 2014, www.abs-cbnnews.com/nation/08/07/14/marwan-alive-has-serious-implications-trillanes. ASG has also been known to harbor JI militants in its dense jungle landscape. In March 2010, the Indonesian government formally requested that Philippine law enforcement track down an Indonesian national and JI trainer of the MILF and ASG known only as Sanusi. Sanusi allegedly perpetrated sectarian violence in the Sulawesi region of Indonesia, including the beheadings of three school girls in 2007.Zachary Abuza, “The Philippines Chips Away at the Abu Sayyaf Group’s Strength,” CTC Sentinel 3, no. 4 (April 3, 2010), https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-philippines-chips-away-at-the-abu-sayyaf-group%E2%80%99s-strength.

In 2003, a key JI leader and most-wanted terrorist, Zulkifli Abdhir, a.k.a Marwan, went into hiding in the ASG-controlled region in the Philippines.“Marwan Alive Has Serious Implications: Trillanes,” ABS-CBN News, August 7, 2014, www.abs-cbnnews.com/nation/08/07/14/marwan-alive-has-serious-implications-trillanes. In February 2015, DNA evidence confirmed that Marwan had been killed after a 12-hour bloody gunfight with the Philippine police’s elite Special Action Force (SAF), during which 44 members of the SAF were killed.Tim Hume, “Man Killed in Philippines Raid Was Wanted Terror Suspect Marwan, DNA Indicates,” CNN, February 5, 2015, http://www.cnn.com/2015/02/05/world/philippines-marwan-dna-positive/. However, a Philippine intelligence chief has asserted that 10 to 12 JI members continue to reside among ASG in the southern Philippines.“Marwan Alive Has Serious Implications: Trillanes,” ABS-CBN News, August 7, 2014, www.abs-cbnnews.com/nation/08/07/14/marwan-alive-has-serious-implications-trillanes.

Many of ASG’s disaffected founding members left the MNLF in March 2007, under the tutelage of radical leader Habier Malik.Zachary Abuza, “The Philippines Chips Away at the Abu Sayyaf Group’s Strength,” CTC Sentinel 3, no. 4 (April 2010), https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/the-philippines-chips-away-at-the-abu-sayyaf-group%E2%80%99s-strength. In 1986, MNLF was able to negotiate a degree of self-rule in a newly established Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM). ASG has not had formal ties with the MNLF since the MNLF began political discussions with the Philippine government in the mid-1980s.James Brandon, “Syrian and Iraqi Jihadis Prompt Increased Recruitment and Activism in Southeast Asia,” CTC Sentinel 7, no. 10 (October 2014), https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/syrian-and-iraqi-jihads-prompt-increased-recruitment-and-activism-in-southeast-asia.

Another off-shoot of the MNLF is the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), which separated from the MNLF in 1984 amidst disagreement over the MNLF’s peace negotiations with the Philippine government.J.M., “The Biggest Fighter Among Many,” Economist, January 27, 2014, http://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2014/01/peace-southern-philippines?zid=312&ah=da4ed4425e74339883d473adf5773841. Though the MILF proved too moderate and secular for ASG, there are some radical elements within the MILF that have maintained ties.Zack Fellman, “Abu Sayyaf Group,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 2011, http://csis.org/files/publication/111128_Fellman_ASG_AQAMCaseStudy5.pdf. Like the MNLF, the MILF has officially distanced itself from the ASG. However, it is believed that some units of the MILF still cooperate with ASG members, providing refuge for them and their JI counterparts.Thomas Lum, “The Republic of the Philippines and U.S. Interests – 2014,” Congressional Research Service, May 15, 2014, http://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL33233.pdf.

Extremists: Their Words. Their Actions.

Fact:

On May 8, 2019, Taliban insurgents detonated an explosive-laden vehicle and then broke into American NGO Counterpart International’s offices in Kabul. At least seven people were killed and 24 were injured.

Get the latest news on extremism and counter-extremism delivered to your inbox.