Thousands of people from Europe and North America have left their homes to fight alongside al-Qaeda and ISIS. Others have stayed behind to carry out attacks in France, Belgium, the United Kingdom, the United States, and other countries in the name of extremist ideologies.

Media and government officials have traced these foreign fighters and lone wolves to specific areas. CEP’s Extremist Hubs resource examines a list of the neighborhoods, cities, and states that Western news outlets, mayors, and other government officials have labeled as “hotbeds of extremism” or “extremism hubs.” CEP also included areas that are reported hotbeds of far-right, ethno-nationalist extremism.

This resource is not exhaustive, but is instead meant as an overview of some of the areas that have populated terrorism-related news in recent years. Each profile includes a summary of recent extremist-related activity and the reported origins of the area’s designation as a so-called extremist hub. In some cases, national or local governments have taken action to curb extremism in these neighborhoods. Where applicable, the profile links to CEP’s associated country report to provide a broader overview of extremism in that country and government countermeasures.

Key Findings

CEP has identified 10 areas (neighborhoods, cities, and states) in North America, Australia, and Europe of particularly concentrated or heightened extremist activity.

In four of the 10 cases CEP examined, community leaders and government officials have identified high unemployment rates—particularly among youth—as a cause of radicalization.

Among other solutions, local and national governments have sought to boost cooperation between law enforcement and community groups in order to stem radicalization. These efforts are—as in the case of Minnesota—sometimes viewed with suspicion by local communities.

Profiles

Parramatta

Australian counterterrorism expert Greg Barton labeled the Sydney suburb a “hot spot for extremism.”On October 2, 2015, then-15-year-old Iranian immigrant Farhad Jabar shot and killed police accountant Curtis Cheng while he was leaving the main police station in Parramatta. Afterward, Australian counterterrorism expert Greg Barton labeled the Sydney suburb a “hot spot for extremism.” Dr. Amarnath Amarasingam, of Canada’s University of Waterloo, told the Sydney Morning Herald that Jabar was part of a global social media network targeting disenfranchised youth. According to Barton, extremists in Parramatta are increasingly seeking out younger recruits. (Sources: Associated Press, New York Times, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Sydney Morning Herald)

Two extremist groups—Street Dawah and the Shura—have reportedly used the Parramatta Mosque to target Australian youth. Police have also directly linked many of the homes that were part of a 2014 series of terrorism raids to the Parramatta mosque. Street Dawah was previously led by Australian ISIS recruiter Mohammad Ali Baryalei, who reportedly died fighting in Syria in 2015, though the Australian government could not confirm his death. Ahmad Moussalli, who was killed fighting in Syria in 2015, also belonged to the Street Dawah movement. Parramatta’s local council banned the group from operating on the streets of Parramatta after receiving complaints that they were converting random members of the public to Islam in spontaneous street ceremonies. (Sources: New York Times, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Daily Mail)

At least three other Parramatta Street Dawah preachers have reportedly died in Syria in the past few years. After the death of Sheik Mustapha al Majzoub in Syria in August 2012, the Street Dawah Australia Facebook page posted a tribute to the man they called “Our Beloved Brother/Teacher.” (Source: Daily Mail)

Parramatta Muslim leaders have spoken out against radicalization in their community and called for better integration of the Muslim community. A week after the October 2015 police attack, Parramatta Mosque chairman Neil El-Kadomi reportedly gave a sermon telling extremists that if they don’t like Australia, they should get out. Australia Post CEO Ahmed Fahour called for integrating Muslim youth into society and providing economic opportunity to decrease radicalization. “Give these kids a job. When you feel included, then they’re not prone to these mad people who then radicalise them and take them and give them a sense of belonging somewhere else,” he told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. In 2014, Parramatta had a youth unemployment (ages 15 to 24) rate of 16.8 percent, the highest in New South Wales. As of April 2016, Parramatta’s youth unemployment had dropped to 9.9 percent, below the state average of 12 percent. Government figures did not include a breakdown by religion. In August 2016, Fahour again called for “economic and social policies that make us all love being Australians.” (Sources: Sydney Morning Herald, Telegraph, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Daily Telegraph, Sydney Morning Herald, Financial Review)

Dr. Clarke Jones, director of the national counter-radicalization center Australian Intervention Support Hub, said in October 2015 that economics was just one factor in the radicalization of Australian youth. He pointed to discrimination and feelings of persecution by authorities among Muslim immigrants, as well as language barriers in schools and media highlights of Muslims being mistreated overseas, such as in Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq or the U.S.-run Guantanamo Bay facility in Cuba. “In all these sorts of areas Muslims have been oppressed and Islamic State is now giving the false impression that they can act out against this,” Jones told the Australian news website News.com.au. (Source: News.com.au)

In November 2015, the New South Wales government announced $50 million in allocations to prevent radicalization in schools. The government’s tactics include training for school counselors to better identify vulnerable young people. (Source: SBS)

Return to Top

Molenbeek and Schaerbeek

The international media—as well as Belgian government officials—have labeled these two suburbs of Brussels as extremism hotspots. According to the British newspaper Daily Express, Belgian undercover investigative journalist Hind Fraihi “first unearthed the cradle of terrorism” in Molenbeek in 2005. In November 2015, Molenbeek Mayor Francoise Schepmans dubbed her borough a “breeding ground for violence.” A November 2015 op-ed in the Guardian described Molenbeek as “Europe’s jihadi central.” The EUobserver online newspaper called the suburb a “jihadist hotspot” in September 2016, while France 24 cited an expert who declared Molenbeek an “Islamist pit stop.” In November 2015, Belgian Prime Minister Charles Michel called for a crackdown on Molenbeek, saying, “Almost every time there is an Islamist attack], there is a link to Molenbeek.” (Sources: Daily Express, Reuters, Guardian, EUobserver, France24,

In February 2016, Belgian police arrested 10 people belonging to a suspected ISIS recruitment cell during a series of raids in Molenbeek, Schaerbeek, and two other Brussels suburbs.Authorities have linked Molenbeek to at least four attacks within two years: The November 2015 Paris attack assailants Abdelhamid Abaaoud, Salah Abdeslam, and Ibrahim Abdeslam were all raised in Molenbeek; suspected August 2015 train assailant Ayoub El Khazzani also resided in Molenbeek; and May 2014 assailant Mehdi Nemmouche reportedly passed through Molenbeek. (Sources: New York Times, Guardian, New York Times, New York Times, BBC News, BBC News, Guardian)

Molenbeek has also been a source of foreign fighters who have left Belgium to join insurgent movements in Syria and Iraq. As of August 2016, 457 Belgians had gone to fight in Iraq and Syria, according to official government figures. Of those, 50 came from Molenbeek, according to a breakdown of the numbers published that month by the Belgian magazine Knack. In terms of the number of Belgian foreign fighters produced, Molenbeek was second only to Antwerp, from which 97 fighters originated. Another 16 attempted foreign fighters from Molenbeek were arrested before they could leave the country. (Sources: Pieter Van Ostaeyen, Pieter Van Ostaeyen, Guardian, Washington Post, Reuters)

According to head of CEP in Brussels Roberta Bonazzi, “there are several other neighborhoods and towns in Belgium exhibiting the same high levels of radicalization.” About two miles northeast of Molenbeek is Schaerbeek, another Belgian suburb that the media have labeled as an extremist hotbed. Out of Schaerbeek’s 130,000 residents—a mix of immigrants, many from Turkey and Morocco—an estimated 35 have gone on to join insurgent groups abroad, with another 12 attempting, but failing, to do so. In addition to producing a relatively high number of foreign fighters compared to other European neighborhoods, Schaerbeek is noted for producing a number of infamous domestic terrorists. In March 2016, police discovered a nail bomb, explosives, bomb-making chemicals, and an ISIS flag in a Schaerbeek apartment. Schaerbeek native and alleged ISIS bomb-maker Najim Laachraoui was one of three suicide bombers who attacked the Brussels airport and a metro station that month. According to Flanders Today contributing editor Alan Hope, “A visit to Schaerbeek is always on the cards when there's a major criminal investigation.” (Sources: VOA News, USA Today, Pieter Van Ostaeyen, Washington Post)

Observers have pointed to high unemployment—reportedly 27 percent in Molenbeek and 22 percent in Schaerbeek among people ages 15 to 29 as of April 2016—as a key factor in the radicalization of these suburbs. According to the Brussels-based thinktank Egmont Institute, the average age of Belgium jihadists is between 20 and 24. One in two Moroccan men in Molenbeek are reportedly unemployed. French Cities minister Patrick Kanner lamented Molenbeek as “a concentration of enormous poverty and unemployment” where “public services have practically disappeared, it’s a system where politicians have thrown in the towel.” CEP analysts in Brussels have noted that these factors, among others, have made it easier for radical Islamists to target areas like Molenbeek. (Sources: Washington Post, CBS News, Politico, Haaretz)

Return to Top

Aarhus

In 2014, Denmark was reportedly the largest per capita European contributor of foreign fighters to the Middle East. Observers have pointed to Aarhus—Denmark’s second largest city—as a main source of foreign fighters. Approximately 31 people have left Aarhus to fight in Syria since 2012, constituting an estimated 25 percent of Denmark’s foreign fighter population. A February 2015 Foreign Policy blog called the northern Danish city of 300,000 a “Scandinavian hub of jihadi recruitment.” An August 2015 New Republic piece on Omar El-Hussein—who in February 2015 attacked Copenhagen’s Krudttønden cultural center during a visit by a controversial Swedish cartoonist—made special mention of Aarhus as a source of many of the country’s foreign fighters. (Sources: New York Times, NBC News, Foreign Policy, New Republic)

By September 2014, authorities in Aarhus were in the process of rehabilitating most of the 15 Danish foreign fighters that ha re-entered Denmark from Syria.In September 2014, leaders of Aarhus’s Grimhoj mosque openly declared their support for ISIS. Danish police began investigating the mosque in July 2014 after a video emerged of the mosque’s imam, Abu Bilal Ismail, calling on God to “destroy the Zionist Jews.” The mosque is also reportedly a haven for Danish jihadists. Twenty-two of the more than 100 Danish foreign fighters who have gone to fight in the Middle East had previously worshipped at Grimhoj. The mosque came under further fire in February 2016 after a hidden camera taped Imam Abu Bilal Ismail calling for women adulterers to be stoned to death. Ismail said, “If a married or divorced woman engages in fornication, and she is not a virgin, she should be stoned to death.” He also asserted that anyone who kills a Muslim should be killed, and that apostates (those who leave Islam), should also receive the death penalty. The video sparked renewed calls for authorities to shut down the mosque. (Sources: Local, Newsweek, TV2, Local)

Since early 2014, Aarhus police and welfare services have run a rehabilitation program for returning foreign fighters known as the “exit program for radicalized citizens.” The initiative offers medical treatment for war wounds and psychological trauma. The program also assists returning fighters with finding work or resuming education. Aarhus officials launched the initiative after authorities in Aarhus discovered the relatively high percentage of Danish foreign fighters that originated from the city since 2012. Only one Danish citizen left for Syria in 2014. According to an April 2016 report by the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism think-tank, 62 Danish foreign fighters—50 percent of the country’s total—have returned to the country. (Sources: New York Times, Copenhagen Post)

By September 2014, authorities in Aarhus were in the process of rehabilitating most of the 15 Danish foreign fighters that had re-entered Denmark from Syria. Police and the Danish Security and Intelligence Service screen returnees to Denmark upon their arrival back in the country. Rather than arrest the returning foreign fighters, authorities provide returnees with mentors to help them separate militancy from Islam. According to Aarhus police officer Allan Aarslav, the police’s “first priority is to make sure you’re prosecuted when you get back. If you get back and want to get a grip on your old life, we can also help you to do that.” Aarhus’s approach to de-radicalization focuses on actions, and does not attempt to change the ideology of the extremists, according to Steffen Nielsen, a member of a multi-agency task force focused on radicalization and discrimination in the city. Nielsen told Al Jazeera in 2014, “We don’t spend a lot of energy fighting ideology. We don’t try to take away your jihadist beliefs. You are welcome to dream of the Caliphate. But there are some means that you cannot use according to the penal code here. You can be al-Shabab all you like, as long as you don’t actually do al-Shabab. [emphasis in original quote]” (Sources: Globe and Mail, Newsweek, New York Times, International Business Times, Washington Post, Al Jazeera)

Return to Top

Lunel

France’s online newspaper the Local reported that Lunel had been “identified as a hotbed for jihadism.”A February 2015 Daily Mail report identified Lunel as “the town that went to jihad” after at least 17 men from the French suburb of approximately 27,000 joined al-Qaeda or ISIS. French media have highlighted Lunel as a source of French foreign fighters since 2014, when a group of 15 to 30 people—including women and children—reportedly left Lunel for Syria. In March 2016, after a French minister said his country was home to 100 Molenbeeks, France’s online newspaper the Local reported that Lunel had been “identified as a hotbed for jihadism.” In January 2015, police arrested five people in Lunel in connection with 20 French citizens who had recently left the suburb of Montpellier to become foreign fighters in Syria. The town is also linked to prominent ISIS member Abdelilah Himich, a.k.a. Abu Suleyman al-Firansi, who moved to Lunel with his family from Morocco as a teenager. Abu Suleyman reportedly joined ISIS in 2014, and allegedly played a central role in the November 2015 Paris massacre and March 2016 Brussels bombings. (Sources: Bloomberg, Daily Mail, Vice, Agence France-Presse, Pro Publica, Local)

Lunel representatives have rejected the town’s reputation as a source of extremism. The Lunel mosque released a statement in October 2014 denying “all assumptions and rumors that the Lunel mosque has initiated or is encouraging a network of jihadis planning to fight in the Syrian conflict or in any other conflict.” After six Lunel residents were killed in Syria in late 2014, Lahoucine Goumri, then-president of Lunel’s Al Baraka mosque at the time, stated: “This is their choice. It is not for me to judge them.” City council member Philippe Moissonier told French media in December 2014 that Lunel was “not a hotbed of jihadists.” Moissonier seemingly reversed his position the following month, telling Agence France-Presse, “When you have 20 young people who leave, six of whom who have been killed and young women (among them) we will never see again, there's a problem.” (Sources: Daily Mail, Vice, Agence France-Presse, New York Times)

According to Moissonier in January 2015, there is a “generation that has become radicalised because it’s (full of) bitterness.” Lunel is one of many banlieues—suburbs—in France that have earned national attention for its exceptional levels of poverty. Mosque leaders in Lunel cite unemployment and discrimination in school and at work as factors in the radicalization of Lunel’s youth. As of January 2015, the town’s unemployment rate hovered at 20 percent, double the French national average. Suburbs like Lunel reportedly have higher percentages of immigrants and Muslims than the rest of the country, according to Bloomberg. French Prime Minister Manuel Valls said in January 2015 that a “territorial, social, ethnic apartheid has taken root in France.” In April 2016, Moissonier said that many have ignored the signs of Islamist radicalization in Lunel. (Sources: Vice, Agence France-Presse, Bloomberg, Financial Times)

Return to Top

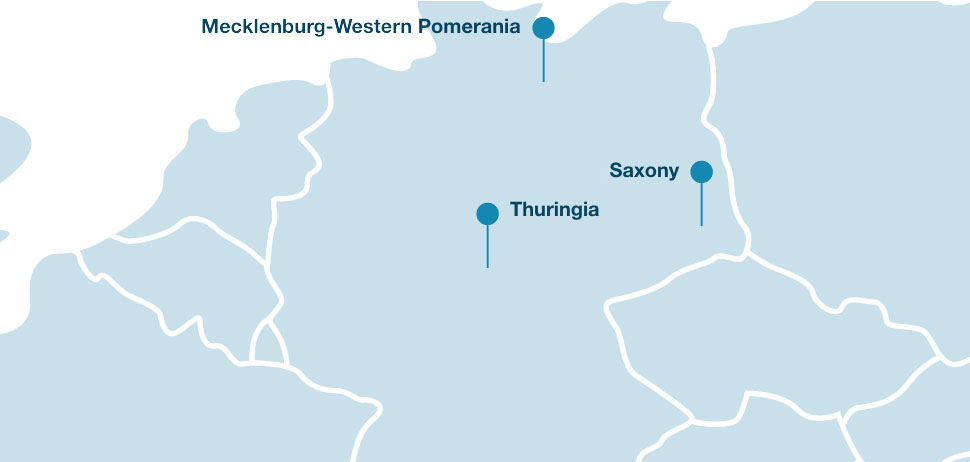

Eastern German States of Saxony, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, and Thuringia

The extreme right is expanding in Germany, according to a July 2016 report by Germany’s Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (BfV) intelligence service. Xenophobic crimes in Germany increased by 42 percent from 2014 to 2015. The east German state of Saxony has “the highest proportion of organized neo-Nazis in Germany,” according to a September 2016 Deutsche Welle report. Writing in September 2015, Saxony Minister-President Stanislaw Tillich acknowledged that “there is a far-right scene in Saxony that should not be underestimated: people who trample on our values and attack democracy, who stir up hatred of others and are violent.” Spiegel Online reported in 2012 that the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania “has a longstanding reputation as a hotbed of xenophobic activity,” while Deutsche Welle wrote in September 2016 that Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania has “an image of being a stronghold of right-wing nationalists.” The Local reported “growing neo-Nazi activity” in Thuringia in 2010, as far-right crimes in the state had almost doubled since 2005. In August 2016, Thuringian parliamentarian Andreas Bühl said the state is at risk of becoming a “safe haven” for neo-Nazis and other far-right extremists. (Sources: Deutsche Welle, Deutsche Welle, Spiegel Online, Deutsche Welle, Deutsche Welle, Deutsche Welle, Local, Deutsche Welle)

Several extreme-right groups operate in these areas, capitalizing on anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim sentiments.Several extreme-right groups operate in these areas, capitalizing on anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim sentiments. The anti-Islamic group Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the West (PEGIDA) launched in Saxony’s city of Dresden in October 2014, and holds weekly anti-immigrant demonstrations. In October 2015, German Vice-Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel accused PEGIDA of using the “battle rhetoric” of the early Nazi Party. Hajo Funke, a political scientist in Berlin, told Spiegel Online in 2012 that neo-Nazis have a higher profile in Saxony than any other German state. According to the lobby group Business for an Open-Minded Saxony, “Saxony’s reputation and image has suffered through the xenophobic assaults and demonstrations.” In November 2016, the Financial Times attributed declines in tourism and economic growth in east Germany to rising far-right extremism and anti-immigrant demonstrations. In July 2016, PEGIDA announced its intentions to create a political party, but added that it did not want to draw votes away from the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party. (Sources: Telegraph, Telegraph, Reuters, Deutsche Welle, Financial Times, Spiegel Online, Guardian, Guardian)

Alternative for Germany (AfD) is a right-wing nationalist political party founded in 2013 on anti-immigration and anti-Islam platforms. AfD founder Frauke Petry is a native of Saxony and as such the party has found stronger support in eastern German states than in the west. In May 2016, AFD introduced its “Islam does not belong in Germany” platform. Petry has also called for destigmatizing the word “völkisch”—a word often associated with Nazism that is used to describe people as belonging to a specific race. Thuringia AfD leader Björn Höcke maintains local support for his xenophobic rhetoric, such as his belief that the “reproductive strategies” of Africans are diluting the ethnic-German population. In May 2016, the AfD protested the construction of Thuringia’s first mosque. Höcke’s success in Thuringia led Funke to declare that the AfD “is in the hands of radicals now.” (Sources: BBC News, New York Times, Politico, Deutsche Welle, Deutsche Welle, Deutsche Welle, Reuters, Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (BfV), International Business Times, Berliner Zeitung, Reuters, Deutsche Welle, Deutsche Welle)

By August 2016, Thuringia had hosted 14 extreme right-wing music festivals that year, according to the German Interior Ministry. Thuringia has its own offshoot of PEGIDA called Thügida. The group organized an April 2016 rally on Adolf Hitler’s birthday in Jena, Thuringia, during which some 300 torch-carrying demonstrators engaged in violent clashes with anti-fascist protesters. The neo-Nazi group Thuringia Home Defense reportedly has 162 members. The German government has reportedly tried to coopt members of the group. A 2016 neo-Nazi-related murder trial revealed that 43 of the members are officially paid informers for German security services, but the money—more than $1 million—has been used to fund neo-Nazi activities. (Sources: Deutsche Welle, International Business Times, McClatchyDC)

The AfD came in second in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania’s September 2016 parliamentary elections, giving the AfD representation in 10 of Germany’s 16 states. Ahead of the September 2016 elections, Germany’s federal family minister, Manuela Schwesig, accused the AfD of “fraternizing officially with the neo-Nazis.” Schwesig also said that the AfD in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania is largely indistinguishable from Germany’s far-right National Democratic Party (NPD), which has ties to the neo-Nazi movement. As of the September 2016 elections, NPD is no longer represented in any of Germany’s states. Nonetheless, the NPD remains active, particularly in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania where the group is “rooted in parts of civil society – it’s like a base they can always count on for the next few years,” journalist Robert Ackermann told Deutsche Welle that month. (Sources: Deutsche Welle, Deutsche Welle)

In August 2016, German authorities began surveillance of Identitare Bewegung (IBD)—the Identity Movement for Germany, an anti-Islamic and xenophobic movement with its origins in France. In August 2016, German security services began monitoring IBD in Saxony and eight other states. IBD supporters have reportedly interwoven themselves with PEGIDA. Authorities noted the presence IBD flags and propaganda during and following a July 2016 PEGIDA rally in Leipzig, Saxony. (Sources: World Politics Review, Reuters, Deutsche Welle)

According to the NGO Mut Gegen Rechte Gewalt (Courage Against Right-Wing Violence), there were 561 attacks against refugees in Saxony between January 2015 and October 2016.

Groups like PEGIDA have made anti-Muslim immigration a central focus. For example, one PEGIDA protest leader at a February 2016 rally declared, “We must succeed in guarding and controlling Europe’s external borders as well as its internal borders once again.” An October 2016 PEGIDA rally in Dresden to mark the group’s second anniversary drew an estimated 6,500 to 8,500 people. (Sources: Foreign Affairs, Reuters, Reuters)

Neo-Nazi violence and sympathies have steadily risen in Saxony since Germany’s 1990 reunification. Neo-Nazi groups began organizing annual marches in Dresden in 1999. Between 2000 and 2007, the Saxony-based far-right terrorist group National Socialist Underground murdered 10 people, mostly Turkish immigrants, in what Spiegel Online called a “nationwide killing spree.” In Saxony’s June 2008 municipal elections, the neo-Nazi NPD won 5.1 percent of the vote, though the group has since lost its representation. (Sources: Spiegel Online, Guardian, New York Times, New York Times)

German counter-extremism professionals have likened right-wing extremism to Islamic extremism. According to Thomas Mücke of the Berlin-based Violence Prevention Network (VPN), “They are both fascist ideologies. One is using a certain idea of the nation, the other is using religion as its instrument.” VPN and groups like it developed individually tailored interventions for neo-Nazis, which they now use to address Islamic extremism as well. However, the neo-Nazi movement has shifted to include anti-immigrant propaganda and violence, such as a September 2016 street fight between about 100 neo-Nazis chanting “Bautzen for Germans only” and 20 asylum-seekers in Saxony’s Bautzen. According to Marcus Kemper of the Saxon cultural office, right-wing extremist assaults increased by 90 percent between 2014 and 2016. Kemper blamed the anti-immigrant stance of groups like PEGIDA, which he called “a catalyst for neo-Nazis and other racists.” (Sources: Foreign Affairs, Christian Science Monitor, Daily Mail, Deutsche Welle)

The district of Görlitz in the city of Genau has sought to reduce right-wing extremism by changing residents’ perceptions of refugees. The city reported only nine anti-refugee attacks in two years, Foreign Affairs reported in October 2016, compared with 161 in nearby Dresden during the same period. Since August 2014, local authorities have implemented the so-called Görlitz Model to encourage dialogue between residents and refugees. Görlitz officials have gone door to door to talk to residents while replacing phrases such as “asylum seeker” with “new neighbor.” They then moved refugees from shelters to apartments. According to the plan’s architect, Görlitz Magistrate Werner Genau, “People don’t ‘see’ Syrians because they just mind their own lives as do all the others.” (Source: Foreign Affairs)

Return to Top

Luton

The British city of Luton in the county of Bedfordshire is known as a bastion of both Islamic and far-right extremism.The British city of Luton in the county of Bedfordshire, 35 miles north of London, is known as a bastion of both Islamic and far-right extremism. Luton became a hub for Muslim immigrants in the 1960s. The media labeled Luton a “hotbed of extremism” in the 1990s after the revelation that one of the men in a 1998 terrorist plot in Yemen had lived in Luton. The Guardian refers to Luton as a “centre of extremism.” British police label Luton a “tinder box” because of the presence of both Islamic extremists and right-wing groups such as the English Defence League (EDL), which has led to violent clashes between the two. (Sources: International Business Times, Daily Mail, Guardian, BBC News)

The Guardian reported in November 2015 that Scotland Yard’s counter-terrorism command had arrested, charged, or taken other action against 15 people from Luton’s Bury Park neighborhood in the preceding 12 months. Former Luton resident Abu Rahin Aziz reportedly met and learned to make bombs from Abdelhamid Abaaoud, the ringleader of the November 2015 Paris attacks. Aziz died in a July 2015 U.S. airstrike targeting ISIS in Raqqa, Syria. (Sources: Guardian, Guardian)

The banned extremist group al-Muhajiroun, created by radical preachers Omar Bakri Mohammad and Anjem Choudary, first met in Luton, as did the planners of the July 7, 2005, bombings. Support for ISIS in Luton has been well-documented. In 2014, Luton-based members of Choudary’s al-Muhajiroun group reportedly distributed pro-ISIS fliers in London. The following year, in June 2015, speakers at two separate events in Luton spoke out in support of ISIS and against “the kuffar.” (Sources: International Business Times, Evening Standard, BBC News)

Other Luton residents have also been implicated in domestic terrorist plots. For example, in April 2016, authorities convicted Luton delivery driver Junead Khan of planning a terror attack on U.S. forces in Britain. Luton police arrested four men in December 2015 on suspicion of terrorism-related activities. (Sources: Daily Mail, Guardian)

Far-right groups have reportedly labeled Luton’s Bury Park an “Islamic ghetto,” while initiating their own anti-Islamic extremism. The EDL emerged in 2009 to take a stand against radical Islam in Britain, according to its leaders. The EDL has led “aggressive rallies” at Luton’s Central Mosque. In May 2009, right-wing extremists firebombed an Islamic center in Luton, reportedly as revenge for protests against soldiers returning from Iraq. A member of the Facebook group “Ban The Terrorists,” run by a group called “People of Luton,” said he believed the center was bombed because “these Muslim extremists tend to hang out nearby.” In 2016, the right-wing Britain First formed so-called “Christian patrols” in Luton to hand out anti-Islam pamphlets to Muslims. (Sources: Guardian, International Business Times, Daily Star, Daily Mail, BBC Radio, BBC News)

After the January 2015 attacks in Paris, Bedfordshire Police and Crime Commissioner Olly Martins said that officers were trying to prevent the radicalization of 120 Muslims in the county. That October, then-Prime Minister David Cameron announced a new national counter-extremism strategy at Luton’s Denbigh High School. Under the new strategy, parents could apply to have their children’s passports revoked if they suspect radicalization. Anyone convicted of terrorism or extremism would also automatically be banned from working with children. As of November 2015, police reported that not all area schools in Luton were cooperating in countering radicalization. A 20-month undercover operation in Luton resulted in evidence for the August 2016 conviction of three men on charges of inviting support for ISIS. In a separate July 2016 trial, a jury convicted Choudary of inviting support for ISIS. (Sources: Guardian, BBC News, Wall Street Journal)

Return to Top

Minnesota

A September 2015 report by the U.S. House Committee on Homeland Security found that Minnesota led the United States in the number of people who either left or attempted to leave to fight with ISIS. According to the report, Minnesotans comprised 26 percent of 58 sample cases. As the state’s first trial of would-be ISIS foreign fighters began in May 2016, Minnesota Public Radio called the state “home to one of the largest clusters of ISIS defendants in the nation.” In August 2016, then-Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump said that Minnesota’s Somali immigrants represent “a rich pool of potential recruiting targets for Islamist terror groups,” drawing the ire of Minnesota’s Somali community. The U.S. Department of Justice has called Minnesotans, particularly of Somali descent, recruitment targets of ISIS and al-Shabab. (Sources: U.S. House Committee on Homeland Security, Star Tribune, MPR News, Star Tribune)

A September 2015 report found that Minnesota led the United States in the number of people who left to fight with ISIS.Minnesota is home to the largest Somali immigrant population in the United States. Since 2007, at least 20 Somali-Minnesotans have left to join al-Shabab according to the Justice Department. Further, more than 20 Somali-Minnesotans have been charged in U.S. District Court in Minnesota on terrorism charges. Authorities have arrested at least nine Minnesota men trying to join ISIS since 2014. Other Minnesota men have attempted domestic attacks on behalf of foreign terrorist organizations. In one case, on September 17, 2016, 20-year-old Somali immigrant Dahir Ahmed Adan went on a stabbing rampage at a Minnesota mall, wounding 10 people. Authorities said Adan had self-radicalized and transformed from a high-achieving college student to failing out of college “almost overnight.” After the attack, ISIS reportedly claimed Adan as its “soldier.” (Sources: Star Tribune, U.S. Department of Justice, Yahoo News, Associated Press, Agence France-Presse)

In June 2016, Minnesota’s legislature passed a resolution calling for $2 million in grant money for Somali-American youth development to counter radicalization. Despite bipartisan support, the resolution was attached to other legislation, which Governor Mark Dayton vetoed in June 2016. Law enforcement works alongside Somali community leaders on other counter-radicalization programs, such as the “Building Community Resilience” pilot program in Minneapolis-St. Paul. Beginning in 2014, the U.S. Attorney’s office and local law enforcement has met with religious leaders, mental health professionals, youth leaders, mothers, and others to discuss communal concerns and identify the causes of radicalization. They then developed action plans to intervene in the early stages of radicalization. In March 2016, under the Building Community Resilience program, the Minnesota non-profit Youthprise distributed $300,000 in federal grants to six Somali-American community groups to combat radicalization among Somali youth. A group called the Somali-American Task Force is responsible for implementing the Building Community Resilience pilot program. (Sources: Star Tribune, U.S. Department of Justice, Star Tribune)

The FBI arrested American-born Abdullahi Yusuf in May 2014 at the Minneapolis airport as he attempted to leave for Syria. In September 2016, Yusuf’s parents credited the FBI for saving their son’s life. But not all in Minnesota’s Somali community approve of government and communal counter-radicalization efforts. In May 2015, the Council on American-Islamic Relations-Minnesota released a statement on behalf of almost 50 mosques condemning the Building Community Resilience pilot program for mixing “policing and counter-terrorism efforts with social services and outreach targeting only one religious and ethnic community.” The statement further accused authorities of stigmatizing communities “through the use of surveillance, informants, and other targeting of Muslim communities not connected to any suspected wrongdoing.” Minnesota’s Star Tribune paper has run an ongoing series called Radical Intervention,” highlighting counter-radicalization strategies in Minnesota and abroad. An August 2016 editorial in the paper praised current programs while calling on communal leaders and officials to continue developing new strategies. (Sources: NPR, MPR News, CBS News, Star Tribune)

Return to Top Australia

Australia

For more information on extremism in Australia

For more information on extremism in Australia Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

France

France

Germany

Germany

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

United States

United States