Since the end of World War II, extremist groups have carried out numerous acts of violence in Europe in the pursuit of political and religious objectives. The policy responses from European governments to these terrorist acts have too often been weak, ad hoc, and have failed to deter future attacks or dismantle terrorist networks.

These failed strategies—including negotiations that free imprisoned terrorists, ransom payments, and abandoned investigations—have played into the hands of terrorist actors, empowering them to carry out further attacks. As Europe grapples with resurgent attacks by ISIS, al-Qaeda, and other non-state actors, governments will need clear, consistent, and proactive counterterrorism strategies in order to preclude and contain the threat.

Overview

In the years immediately following World War II, Europe saw the emergence of far-left (Marxist-Leninist-Maoist) and far-right (neo-fascist) terror groups such as the far-left Red Army Faction in West Germany and the Red Brigades in Italy, and the far-right French and European Nationalist Party in France. The nature of terrorism shifted in the 1960s with the emergence of secular, nationalist Palestinian terror groups in Europe, including the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and the Abu Nidal Organization. Both groups carried out attacks inside Europe in an attempt to draw international attention to the Palestinian cause.

The responses of European authorities to Palestinian terror unfortunately did little to deter additional acts of terrorism on European soil. Worse, it boosted the profile of Palestinian terror groups. In the 1980s, no other region outside the Middle East experienced as much Middle Eastern terrorism as Western Europe. Violence continued through the 1990s, and in 2004 and 2005, al-Qaeda carried out attacks in Madrid and London, respectively. In recent years, ISIS has exported violence to the continent, inspiring lone-wolf attacks and coordinating multi-person operations. (Sources: Pluchinsky (Conflict Quarterly))

According to terror analyst Dennis Pluchinsky, Middle Eastern terror groups select European targets for a number of reasons. Among them are the “geographic proximity [to the Arab world] and compactness” of Western Europe, which offers “excellent transportation facilities, and relatively easy cross-border movement.”

Europe's "lax" attitude toward radical Islam:

- Provides asylum to Islamists regardless of past crimes

- Immigration laws are rarely enforced

- Little censorship of hateful clerics

- Recruitment to terror organization rarely prosecuted

In the past few decades, Islamists have taken advantage of Europe’s “lax” attitude toward radical Islam. According to author Lorenzo Vidino, European countries have provided asylum to Islamists regardless of past crimes, and immigration laws have rarely been enforced. There is little censorship of hateful clerics—who are able to preach freely within their communities—and recruitment to terror organizations has rarely been prosecuted. (Sources: Pluchinsky (Conflict Quarterly), Al Qaeda in Europe, Lorenzo Vidino, p. 19)

Beyond the geographical and political factors leading to the selection of European terror targets, European counterterrorism strategies have made Europe less safe. Specifically, authorities’ efforts to protect citizens in the short-term—including making ransom payments and a willingness to enter into negotiations with terrorists—have only emboldened terror groups, weakening public security in the longer term.

A lack of planning and prioritization among political units and security agencies has resulted in security lapses and botched intelligence sharing. Incredibly, several European governments have even chosen to ignore attack warnings in order to protect diplomatic or economic equities. For example, since the Iranian revolution, several European countries have turned a blind eye to Iranian sponsored terror on their soil in order to preserve economic interests and trade ties with the Islamic Republic.

In the past few years, European governments have failed to appropriately connect seemingly distinct jihadist attacks to an extensive ISIS and al-Qaeda network on the continent. As a result, European authorities failed to synthesize information that might have prevented the November 2015 Paris attacks and March 2016 Brussels bombings, respectively.

For example, European authorities failed to connect Abdelhamid Abaaoud—a Belgian ISIS operative trained in Syria and the mastermind of the Paris attacks—to a series of attacks in Europe beginning in 2014, including the Brussels Jewish Museum shooting by Mehdi Nemmouche in May 2014; a failed shooting of a church in Villejuif by Sid Ahmed Ghlam in April 2015; and a thwarted shooting and stabbing attack on a high-speed Thalys train from Brussels to Paris by Ayoub El Khazzani in August 2015. (Source: New York Times)

In certain instances, European governments have successfully countered terror activity and dismantled terror networks operating on their soil, as in the case of West Germany’s defeat of the RAF in the 1970s, and the French campaign against the Armed Islamic Group in the 1990s. However, when European governments accommodated terrorist demands or failed to act systematically to confront terrorist actors, they either emboldened terror groups or exposed their citizens to preventable future terrorist violence.

Palestinian Terror in Europe

Since the 1960s, Palestinian terrorists have carried out attacks in multiple European nations. The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), designated by the U.S. in 1997, made its ‘debut’ in Europe in 1968 when three of its members hijacked an El Al airplane en route from Rome to Tel Aviv and diverted it to Algeria. (Sources: Why Terrorism Works, Alan M. Dershowitz, p. 36, U.S. Department of State)

According to author Maria do Céu Pinto, Palestinian terrorists selected Israeli assets in Europe and European targets to punish countries seen as supportive of Israel, free Palestinian prisoners from European or Israeli prisons, and to highlight and bolster international sympathy for the Palestinian cause.

Vicious cycle:

Some Europeans countries have historically consented to the terrorists demands. Unfortunately, these policies led to more hijacking operations.

European countries including Germany, France, Greece, and Italy, consented to the terrorists’ demands—often times freeing imprisoned terrorists—in the hopes that it would provide safety for their citizens. These naïve policies led to a vicious cycle of more hijacking operations to free more prisoners. In Dershowitz’s Why Terrorism Works, he described the European pattern of freeing Palestinian prisoners as a “revolving door system,” in which terrorists are arrested after an attack, released after another attack, and are poised to commit the cycle of violence again. (Sources: Islamist and Middle Eastern Terrorism: a Threat to Europe?, Maria do Céu Pinto, p. 11-14, Pluchinsky (Conflict Quarterly), Why Terrorism Works, Alan M. Dershowitz, p. 98)

The Palestinian terror group “Abu Nidal Organization” carried out numerous kidnapping operations and other violent attacks throughout Europe in the 1970s and ‘80s. Led by Palestinian militant Abu Nidal, the group chose France for many of its attacks. In 1978, the Abu Nidal Organization assassinated PLO representative Ezeddine Qalaq in Paris. Six years later, an Abu Nidal insurgent shot and killed the Emirati ambassador in Paris, Khalifa Ahmad Mubarak. In the 1980s, the terror group waged a series of attacks in Paris on restaurants and shops.

In response, the French government entered negotiations with Nidal and even allowed members of the terror group to attain “scholarships” to study in Paris. The government allowed an Abu Nidal representative to live in France and serve as a contact between the two sides. (Sources: Pluchinsky (Conflict Quarterly), Al Arabiya)

The Austrian government also courted relations with the Abu Nidal Organization after the group targeted an Austrian hotel. The government had an Abu Nidal “secret” representative operating on its soil, and sent a delegation to Baghdad to meet with Abu Nidal himself. (Source: Al Arabiya)

By the early 1970s, Palestinian terror attacks inside Europe had become a regular occurrence. Perhaps the most famous terror attack, the Munich massacre, was perpetrated by the Palestinian group “Black September” during the summer Olympics in West Germany in 1972.

Case Study: The Munich Massacre

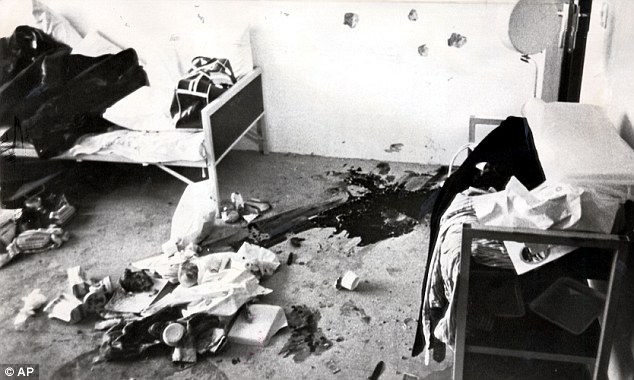

In the early morning of September 5, 1972, eight insurgents from the Palestinian group Black September entered the Olympic compound in Munich, West Germany, killed two Israelis and took nine others hostage. The terrorists demanded the release of 234 Palestinian prisoners from Israeli prisons, as well as the release of West German-held Red Army Faction leaders Andreas Baader and Ulrike Meinhof. (Sources: New York Times, Encyclopedia of Terrorism, Revised Edition, Cindy C. Combs, Martin W. Slann, p. 189)

The Israeli government adhered to its policy of no negotiations with terrorists. But the West Germans, shocked and horrified at the thought of Jews being slaughtered on German soil, immediately sought to assuage the terrorists. In tense negotiations at the Olympic compound, German authorities offered to pay “any price” to release the hostages, though the terrorists said they cared for “neither money nor lives.” The Federal Minister of the Interior, Hans-Dietrich Genscher, offered himself as a replacement for the Israeli hostages, which the terrorists also refused. Instead, the terrorists demanded that the hostages be flown to Cairo. West German authorities feigned agreement but secretly planned to launch a rescue mission at the Fürstenfeldbruck military airport to free the hostages. (Sources: Why Terrorism Works, Alan M. Dershowitz, p. 43, BBC News)

A shootout ensued during the rescue operation and the terrorists, who had landed at the military airport in a helicopter, murdered the nine Israeli hostages onboard. The botched ambush and rescue attempt was carried out by West German police since the West German military was restricted from operating domestically by West Germany’s post-war constitution. Insufficient weaponry and a lack of radio contact between the West German snipers contributed to the failure. Authorities had also underestimated the number of terrorists and failed to provide enough sharpshooters. (Sources: New York Times, New York Times)

The West German government failed to process and share intelligence tips in the months leading up to the attack. Less than two months before the massacre, West German police in the western city of Dortmund sent a telex to BfV—West Germany’s domestic security agency—warning of “presumed conspiratorial activity by Palestinian terrorists.” The telex connected the terrorists to neo-Nazis inside Germany, who were later revealed to have provided logistical assistance to the Palestinians. (Source: Spiegel)

Less than one month before the attack, the West German government reportedly ignored a warning of a terror attack at the upcoming Olympic Games. On August 14, 1972, a West German embassy officer in Beirut heard that an “incident would be staged by…the Palestinian side during the Olympic Games....” The message was forwarded to Bavaria’s state intelligence agency, with recommendations to take full precautions. At the same time, West German officials refused Israel’s request to provide security for the Israeli athletes. (Sources: Spiegel, Why Terrorism Works, Alan M. Dershowitz, p. 42)

Three of the attackers were captured by West German authorities immediately following the attack. However, the West German Chancellor Willy Brandt reportedly reached a deal with the Palestinian terrorists whereby a number of Palestinians would stage a hijacking of a Lufthansa airplane and demand the release of the Munich murderers. Critics suspected that the ruse was sought to effectuate the release of the prisoners while avoiding a real terror attack to accomplish the same purpose. The West German government released the prisoners, who returned home as heroes. Israeli security agents later hunted down and killed many Black September operatives believed to have been involved with the massacre. (Sources: Why Terrorism Works, Alan M. Dershowitz, p. 43-44, TIME)

The larger collective European response to the killing of 11 hostages in Munich was increased support for Palestinian issues at the United Nations and attention drawn to the Palestinian cause internationally. Black September celebrated the operation and scorned West Germany’s feeble response. “The choice of the Olympics, from the purely propagandistic standpoint, was 100 percent successful,” noted a Black September communique after the attacks. “It was like painting the name of Palestine on a mountain that can be seen from the four corners of the earth.” (Source: Why Terrorism Works, Alan M. Dershowitz, p. 46)

"The choice of the Olympics, from the purely propagandistic standpoint, was 100 percent successful. It was like painting the name of Palestine on a mountain that can be seen from the four corners of the earth."

Why Terrorism Works, Alan M. Dershowitz, p. 46, Foreign Policy Research Institute

Since the Islamic Republic’s formation in 1979, the Iranian regime has been linked to more than 160 murders of its political rivals around the world. For example, in December 1979, Iranian agents assassinated the nephew of the Shah, Shahriar Shafiq, in Paris. In 1980, a five-person “hit squad” attempted to murder the last Prime Minister before the 1979 Islamic revolution, Shapour Bakhtiar, in Paris. The assassins failed to kill Bakhtiar, instead murdering a policewoman and Bakhtiar’s female neighbor. In 1991, three Iranian agents murdered Bakhtiar in his Paris home. (Sources: IHRDC, PBS)

In 1990, Iranian assassins murdered professor Kazem Rajavi in Switzerland. In late 1992, two men implicated in Rajavi’s murder were apprehended in Paris. Switzerland requested their extradition, but in December 1993, France sent both men back to Iran, citing “reasons connected to our national interests.” It was later revealed that Iran had threatened terror attacks on French targets if France chose to extradite the fugitives—threats that France took “with great seriousness.” A Le Monde report stated, “Appearing to cave in to the threat of terrorism is certainly not the best way to fight it.” (Sources: New York Times, IHRDC)

It appears some European governments have been unwilling to confront Iranian-sponsored terror on European soil out of fear that it will hinder trade with the oil-rich country. Their reluctance to counter Iranian terror may also be tied to a belief that a proactive inquiry into the attacks would lead to aggravation of the Iranian regime and subsequent retaliatory violence.

Case Study: Iranian Assassinations in Austria and Germany

On July 13, 1989, Iranian intelligence agents in Vienna assassinated Abdul Rahman Ghassemlou, the Secretary General of the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI). Ghassemlou had been in Austria to negotiate with Iranian officials on Kurdish rights and self-governance.

On July 13, 1989, Iranian intelligence agents in Vienna assassinated Abdul Rahman Ghassemlou, the Secretary General of the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI). Ghassemlou had been in Austria to negotiate with Iranian officials on Kurdish rights and self-governance.

After the killing, Austrian authorities released the three suspects—Feridoun Mehdi Nezhad, Amir Mansour Bozorgian, and Mohamad Sahraroudi—who then traveled back to Iran. Mohamad Sahraroudi, who was wounded in the attack, was even given police protection until he left Vienna one week after the assassination. During the episode, confusion mounted as Austrian media outlets reportedly disseminated mistaken information. At the same time, competition grew among police units, seemingly leading to inadequate police work. The Austrian government only issued arrest warrants for the suspects four months after the incident, in November 1989. The government later downplayed these blunders as administrative errors. (Sources: Appendix 7: Open Source Information on the Fate(s) of Perpetrators/Conspirators, (Lee Crowther), Agence France-Presse)

Austrian politician Peter Pilz has said that Austria “ceded to pressure to safeguard its economic interests,” implying that Austrian authorities refused to bring the Iranians to justice out of fear that it would hinder trade relations with Iran. (Source: Agence France-Presse)

Austria reportedly remained “stubbornly tight-lipped” about the case, which has not yet been resolved. Though the West German government has linked the assassination to former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Tehran has consistently denied involvement. (Source: Agence France-Presse)

Three years later, in September 1992, Ghassemlou’s successor, Sadegh Sharafkandi, and three of his associates were assassinated at the Mykonos restaurant in Berlin, Germany. A German court began a trial of Iranian suspects in October 1993, and found four Iranian officials guilty of the murders in April 1997. The court found that the murders were ordered by the “highest state levels,” specifically Iran’s Committee for Special Operations to which then-President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei belonged. The verdict led both Germany and Iran to recall their respective ambassadors. Germany also deported four Iranian diplomats. (Sources: UNHCR, CNN, Todays Zaman)

In December 1997, eight months after the German court found Iran’s leadership responsible for the Mykonos assassinations, the German government released two of the operation’s masterminds, who had been sentenced to life in prison. The two prisoners, Kazem Darabi and Abbas Rhayel, were released and deported to Iran and Lebanon, respectively. (Sources: UNHCR, CNN)

German security expert Wolfgang Wieland warned against the early release, stating that Iran would view it as a “weakness of the West” rather than a “generous move on the part of the German penal system.” Hamid Nowzari, a member of a Berlin-based group for Iranian refugees, asserted that the men’s release was “incompatible with Germany’s fight against terrorism.” (Source: Spiegel)

According to the Kurdish media group Rudaw, Germans and Austrians have allowed Iranian assassinations to take place on their soil—as long as the victims were not their citizens—to protect their billions in trade relations with Iran. (Source: Rudaw)

Al-Qaeda and ISIS Terror in Europe

Since its founding in the 1980s, al-Qaeda has carried out numerous attacks inside Europe, including the notorious Madrid bombings in 2004 and the 7/7 bombings in London in 2005. These attacks, following the September 11, 2001, attacks in New York, were reportedly waged in retaliation for Western policies in the Middle East. (Sources: BBC News, Fox News)

After each large-scale al-Qaeda attack, the targeted country reviews its counterterrorism policies and seeks to shore up information-sharing and coordination between domestic intelligence services. Governments also typically tighten security and enact fresh counterterrorism legislation.

But many European countries have also chosen to take part in a dangerous trade: paying ransom for European hostages taken by al-Qaeda, predominantly in Africa, Syria, and Yemen. Between 2008 and 2014, EU governments have paid nearly $165 million to various al-Qaeda affiliates in order to secure the release of European hostages. The payments—which have reportedly reached up to $10 million per hostage—are believed to finance the groups’ recruitment, training, and weapons purchases. (Source: New York Times)

While the United States and Britain have refused to pay ransoms, governments in Europe—most notably France, Spain, and Switzerland—have continued to deliverer some of the largest amounts, often disguised as aid packages. The research on ransom payment suggests that while these funds secure the release of the hostages in question, they financially enable the terror groups and further incite kidnappings of citizens of those countries that are willing to pay. David S. Cohen, the former U.S. Treasury Department’s Under Secretary for terrorism and financial terrorism, said in 2012 that “each transaction encourages another transaction.” (Source: New York Times)

By refusing to pay ransom, the British government avoids the direct financing of terror organizations. However, a lack of vigilance at home enabled al-Qaeda-inspired Islamists to raise money, recruit, and initiate attacks in the past. Prior to 2001, British authorities rarely arrested or extradited such extremists. Following the 9/11 attacks in New York, however, the British government enacted legislation enabling the indefinite confinement of terrorist suspects, though this was reversed by Britain’s highest court in 2004 as an abuse of human law. An unnamed senior European intelligence official described the 7/7 London bombings as “payback time for a policy that was, in my opinion, an irresponsible policy of the British government to allow [al-Qaeda-inspired] networks to flourish inside Britain.” While Britain was by no means responsible for the violence al-Qaeda directed at U.K. citizens, different and more farsighted government policies may have been able to interrupt, or at least better infiltrate, terrorist activities on British soil. (Source: New York Times)

Case study: 7/7 Bombings

On July 7, 2005, al-Qaeda carried out the single most deadly terror attack on British soil, killing 52 people and injuring more than 700 in simultaneous attacks on London’s public transit system. The attack, known as the 7/7 bombings, was perpetrated by four suicide bombers, three of them from West Yorkshire. (Sources: BBC News, BBC)

Intelligence blunders and botched information sharing preceded the 7/7 bombings. The M15 repeatedly questioned the mastermind of the bombings, Mohammed Sidique Khan. But British security concluded that Khan—only involved in terrorist fundraising—was not dangerous enough to warrant surveillance. (Sources: Daily Mail, Cable Spotlight)

Furthermore, the M15 heavily cropped a photograph taken in February 2004 of two terrorists—Mohammed Sidique Khan and 7/7 bomber Shehzad Tanweer—before it sent the photo to U.S. authorities at some point before the bombings. Two months after the photograph was taken, the FBI questioned a jihadist who said that two terrorists—both of whom were later recognized as the men in the photo—had trained with him in a terrorist camp in Pakistan in 2003. As a result of the poorly cropped photo, U.S. authorities were unable to identify the men as the trainees in Pakistan and alert British authorities of the domestic threat they might pose. (Sources: Daily Mail, Standard UK)

If the intelligence on these men were stronger, and the quality of the photo better, the M15 might have been able to identify the men and assess their threat, prompting further investigations that possibly could have prevented the attacks. Lady Justice Hallet condemned the botched information sharing: “I fully expect the Security Service to review their procedures to ensure that good quality images are shown and that whatever went wrong on this occasion does not happen again.” (Sources: Daily Mail, Standard UK)

Following the bombings, the British government drafted new legislation in which “fostering hatred” and inciting terrorism could result in deportation for foreign nationals. Then-Prime Minister Tony Blair asserted: “the rules of the game are changing.” (Source: Guardian)

Case study: November 13, 2015 Paris attacks

ISIS’s November attacks in Paris—which killed 130 people and wounded more than 350—set off a large-scale examination into possible security and intelligence failures. ISIS insurgents targeted the Stade de France, the Bataclan concert hall, and various restaurants in central Paris. The attacks were orchestrated by Belgian-born Abdelhamid Abaaoud, who was killed in a police raid in north Paris five days after the attacks. (Sources: Bloomberg Business, BBC News)

As Paris and the international community reeled in the wake of the brutal night, two areas of potential weakness rose to the forefront of discussion: the Belgian neighborhood of Molenbeek, believed to be a hub of Islamic radicalization—and the poor security on a Greek island where Middle Eastern refugees had been arriving in droves.

In the immediate aftermath of the attacks, French and Belgium authorities turned their attention toward the Brussels suburb of Molenbeek, where a number of the Paris suicide bombers had lived. Jihadists from Molenbeek have been linked to the September 11 assassination of anti-Taliban leader Ahmad Shah Massoud, the 2004 Madrid bombings, the May 2014 shooting at a Jewish museum in Brussels, the January 2015 attacks in Paris, and the August 2015 shooting and stabbing attack on a train from Amsterdam to France. In addition, Molenbeek has supplied a substantial number of Belgium’s approximately 500 foreign fighters. Belgian Prime Minister Charles Michel said after the Paris attacks: “Almost every time there’s a link with Molenbeek. It’s been a form of laisser faire and laxity. Now we’re paying the bill.” (Sources: Guardian, New York Times)

In the past year, Belgium tightened its security and conducted a number of police raids on suspected jihadist cells. Belgium has long sought to identify the “root causes” of terrorism in an attempt to avoid “encroaching on fundamental rights” or unnecessarily stigmatizing the Muslim community. (Sources: Egmont, Council of Europe)

In addition to the possible issue of Belgium’s approach to problems in Molenbeek, critics cited Brussel’s division between national and regional authorities as a possible hindrance to effective intelligence sharing and security and policing practices. Following the Paris attacks, Brussel’s deputy Prime Minister Jan Jambon stated: “Brussels is a relatively small city, 1.2 million. And yet we have six police departments. Nineteen different municipalities. New York is a city of 11 million. How many police departments do they have? One.” Another concern has been the lack of new legislation to counter hate speech as well as recruitment for, and travel to, jihad in Syria. (Sources: Politico, France24)

Poor information sharing among European governments may be a broader issue and possible factor in the failure to thwart attacks. An unnamed senior Brussels-based diplomat told the Financial Times: “Intelligence sharing is really at the heart of the challenge in Europe. There has been a lot of work, particularly after Charlie Hebdo [January 2015], but it has stalled.” (Source: Financial Times)

Another issue is the weak security measures that fail to adequately screen and vet Middle Eastern refugees at the Greek border. At least two of the Paris assailants entered Greece by posing as Syrian refugees. One of the men, known as “Ahmad al Muhammad,” carried a reportedly counterfeit Syrian passport. He is believed to have entered Greece on October 3, 2015, alongside 198 refugees arriving by boat from Turkey. The BBC reported in December 2015 that eyewitnesses saw the mastermind behind the Paris attacks, Abdelhamid Abaaoud, in Greece at the same time that the two insurgents were reported to have arrived. (Sources: France24, BBC News)

In early December 2015, Greece passed emergency legislation to establish five screening “hot spots” on the surrounding Aegean islands where most of the refugees filter in. Refugees are screened by the EU’s border protection agency, Frontex, and fingerprints are shared with the Greek police. Frontex also oversaw the transfer of refugees from Greece to Turkey beginning in early April 2016. (Sources: Guardian, Associated Press, Wall Street Journal)

Months after the Paris attacks, Western media reported that Reda Hame, a Parisian computer technician turned ISIS operative, had told French authorities in August 2015 that ISIS was preparing to attack Europe. Hame even divulged that ISIS operatives were determining which concert hall to strike. Hame told police: “All I can say is that this will happen very soon. It was a real factory out there and they will really try to hit France and Europe.” Three months later, France experienced the worst terrorist attack in its history. (Sources: New York Times, CNN)

Case Study: March 22, 2016 Brussels Bombings

ISIS bombings at Brussels’ Zaventem Airport and Maalbeek metro station on March 22, 2016, killed 35 people and injured more than 300. The first set of bombings at the Zaventem Airport at approximately 7:00 GMT immediately killed 11. Within 20 minutes, Belgian authorities had shut down the roads and trains leading to the airport. One hour later, a suicide bomber attacked the Maalbeek metro station. The failure of state security to suspend all transportation services immediately following the airport bombings enabled the free-roaming terrorist to effectively target the country’s metro system. (Sources: BBC News, Independent)

Amid the shock, authorities scrambled to link the bombings to ISIS’s November 13 massacre in Paris. The mastermind of those attacks, Abdelhamid Abaaoud, had been killed in a police raid on November 18, 2015. However, his childhood friend and fellow Paris gunman Salah Abdeslam—believed to be the sole surviving participant in the Paris attacks—was able to continue plotting before his eventual capture in Molenbeek three days before the Brussels attacks. Soon after Abdeslam’s capture, Belgian Foreign Minister Didier Reynders warned that Abdeslam had told investigators he was planning an attack on Brussels. According to Reynders, Abdeslam was “ready to restart something in Brussels…. [we] found a lot of weapons, heavy weapons, in the first investigations and we have found a new network around [Abdeslam] in Brussels.” (Source: TIME)

Following one of Europe’s biggest manhunts, Belgian police captured Abdeslam in an apartment a few blocks from his family home in Molenbeek on March 28. Abdeslam had managed to evade Belgium’s intelligence and security agencies for four months while hiding in the Belgian capital and actively planning an attack on Brussels. Security experts have pointed to poor intelligence and a fractured police system to explain Abdeslam’s delayed capture. (Sources: New York Times, TIME)

The Belgian government also failed to heed warnings from Turkish authorities about Ibrahim El Bakraoui, one of the two Belgian ISIS operatives who blew themselves up at the Zaventem Airport. In June 2015, Turkish authorities informed the Belgian government of Bakraoui’s capture and detainment near the Syrian border stemming from his role as a foreign fighter for ISIS. Belgian authorities were unable to link Bakraoui to terror activity and did not request his extradition. Bakraoui was thus deported to the Netherlands and was able to travel freely throughout the European Union. Upon the Belgian government’s acknowledgement of this fatal security failure, Interior Minister Jan Jambon and Justice Minister Koen Geens tendered their resignations, though both were denied by Belgian Prime Minister Charles Michel. (Source: Financial Times)

Criticism of Brussels’ police and intelligence units mounted following the attacks. Analysts raised concerns similar to those voiced after the Paris attacks—questioning the ability of Belgium’s fractured political and security entities to adequately meet the terror threat facing the country. The supposed failure of Molenbeek’s Muslims to “integrate” into Belgian society also was cited as an area of concern.

European Counterterrorism Success

West Germany and the Red Army Faction (RAF)

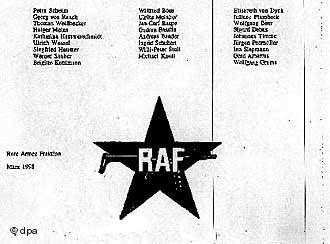

The Red Army Faction (RAF), also known as the Baader-Meinhof Gang, was a far-left Marxist-Leninist group that operated inside West Germany between the 1970s and 1990s. Its members viewed the United States as an imperialist power and the West German government as a continuation of the fascist Nazi party. (Sources: Britannica, Constitutional Rights Foundation)

In September and October of 1977, a period known as the “German Autumn,” the Red Army Faction murdered an industrialist, a banker, and the West German attorney general. On October 13, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) hijacked a Lufthansa airplane, demanding the German government release imprisoned RAF leaders. Five days later, a special West German task force stormed the plane and saved all passengers on board. (Sources: Britannica, Deutsche Welle)

In the early stages of RAF violence, West German authorities moved quickly to form the Bonn Security Group. The group examined the political psychology of the RAF, and studied Marxist and Maoist literature and RAF publications such as The Urban Guerilla Concept by RAF co-founder Ulrike Meinhof. Intelligence authorities scoured the group’s speeches, brochures, and theses, and became well-versed in theories on guerilla warfare and far-left political motives. (Source: Small Wars Journal)

In an attempt to isolate RAF ideology, the West German government initially required all employees to take an oath of loyalty. This policy was soon criticized and abandoned. The West German government then began to grant concessions to the RAF, especially in hostage situations. This reportedly emboldened the RAF into taking more hostages and demanding that RAF leaders be freed from prison. In 1975, West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt overturned the policy of negotiation and concessions. In April of that year, the West German government refused to give into the RAF’s demands after insurgents laid siege to the Swedish embassy in West Germany, killing two diplomats and blowing up the building. The number of RAF hostage-taking incidents reportedly decreased following this event. (Source: Constitutional Rights Foundation)

In 1976, the West German government passed legislation that made it a crime to create a terrorist organization. Proactive intelligence and police work significantly helped to curb the RAF’s success. Authorities leading the effort introduced computer analysis and intelligence sharing—measures that would prove crucial to the fight against the RAF. In addition, detailed analyses of individual RAF members—reportedly including political philosophy, education, upbringing and writings—contributed to the success. By the early 1980s, nearly all group members were deceased or in prison. (Sources: Constitutional Rights Foundation, Small Wars Journal)

France and the Armed Islamic Group (GIA)

The Armed Islamic Group (GIA), an Islamist insurgent group that fought the Algerian government in that country’s civil war, waged a series of attacks inside France in the mid-1990s.

In December 1994, four young GIA members seized an Airbus A300 from the Marseille airport, expressing the desire to fly to Paris. The terrorists demanded that it be filled with 27 tons of fuel, and authorities later determined the group had either planned to explode the plane over Paris or fly it in into the Eiffel Tower. After shooting and killing the hijackers during a rescue operation, French authorities found 20 sticks of dynamite on board the airplane. (Sources: New York Times, APH)

In 1995, the GIA conducted a series of bombings in markets, subways, trains, a Jewish school, and the L’Arc de Triomphe. The attacks killed 10 people and injured more than 400. In December 1996, a GIA bomb in Paris killed four. (Source: APH) The French government brought the perpetrators of these attacks to justice in 1999.

French intelligence acted quickly in detecting and destroying GIA networks inside France. Authorities put immediate pressure not only on the GIA, but on other suspected radical Islamist networks as well. In June 1995, the French government mobilized 400 police officers to make arrests throughout the country. Those officers arrested 131 GIA members and affiliated suspects. This was followed by reprisal attacks perpetrated by terror cells unknown to French authorities. Though taken by surprise, French intelligence was able to round up the existing Islamists within four months. (Sources: Combatting Terrorism Center, Brookings)

Following major al-Qaeda attacks in Spain and Britain in the mid-2000s, scholars posited that France was left untargeted due to successful counterterrorism efforts.

GIA violence jolted France awake to the complex and relatively new strain of Islamist violence inside Europe. French intelligence and law-enforcement authorities successfully collected information on and infiltrated domestic GIA networks. Following major al-Qaeda attacks in Spain and Britain in the mid-2000s, scholars posited that France was left untargeted due to deterrence stemming from its successful counterterrorism efforts against the GIA. (Source: The World Almanac of Islamism, American Foreign Policy Council, p. 532)

The U.K. and Iran: Severed Ties

In 1989, Iran’s founder and then-Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa (Islamic ruling) calling for the death of Salman Rushdie, a British national and author of The Satanic Verses. Rushdie went into hiding and Britain denounced the fatwa. In response, Iran severed ties with Britain, a move which was more symbolic than material, since British officials had evacuated Tehran two weeks prior and had already expelled its Iranian diplomats from London. This is one of the first major instances in which a European country diplomatically punished the Islamic Republic for its terrorist activity. In August 1989, an attempt on Rushdie’s life failed when his would-be killer accidently blew himself up while priming the bomb he meant to use in the assassination attempt. (Sources: Chicago Tribune, Guardian)

Conclusion

In the fight against both domestic and foreign terrorism since World War II, European governments have chosen to submit to terrorists’ demands while failing to anticipate long term implications. Ignored warnings, lack of information sharing, and botched security and intelligence have led to lapses in effective counterterrorism policy, rendering European countries vulnerable to heightened terror activity.

But there are also examples of successful counterterrorism throughout recent European history carried out against both political and religious extremists. Active intelligence gathering, well-planned and coordinated security operations, and intra-governmental and regional intelligence sharing have defeated terror groups.

Governments must work tirelessly to pre-empt the threat with a comprehensive plan. Without proactive polices and a strong front, Europe risks vulnerability.

As the European continent faces a renewed threat of terrorism from Islamist extremists, its governments must work tirelessly to pre-empt attacks with a comprehensive plan that includes significant legislation, superior intelligence, and counter-radicalization and re-habilitation programs. Without proactive policies that present a united and determined front, Europe remains prone to further terror attacks on its soil.