Fact:

On May 8, 2019, Taliban insurgents detonated an explosive-laden vehicle and then broke into American NGO Counterpart International’s offices in Kabul. At least seven people were killed and 24 were injured.

China’s largest province, Xinjiang, could become another front in the global war on terror if the government’s policies against Uyghur separatism do not become more nuanced soon. Marginalized from the country’s economic boom, separatists from the mostly Muslim Turkic-minority Uyghur community have increasingly turned to violence against the Han migrants flooding into the province for work. China has responded harshly in the name of national security, choosing to tie all separatist activity to Islamist extremism rather than address any of the local grievances. As the Council on Foreign Relations notes, this has made it difficult for outside observers, including the media and human rights groups, to distinguish between China’s “genuine counterterrorism” efforts and its “repression of minority rights” in the province.

The Uyghur have reportedly lived in the area continuously since the 3rd century and experienced periods of independence along with foreign rule for many centuries. Long before the People’s Republic of China annexed the province in 1949, the Mongols, Arab caliphates and ancient Chinese dynasties all laid claim for a time to what China calls Xinjiang today and what some Uyghur separatists have re-named Eastern Turkestan.

China is not likely to give up sovereignty in its largest oil and gas producing province any time soon. Economic growth initiatives and a new bullet train into Xinjiang is helping to improve the local economy and integrate the province into China proper. Unfortunately, as some analysts note, many job advertisements explicitly seek Mandarin-only speakers or those who are ethnic Han. This has resulted in some Uyghurs becoming suspicious of the increased Han migration, believing it is a growing threat to their culture and possibly an attempt to dilute the 10 million-strong Uyghur community, which is approximately 45 percent of the total Xinjiang population.

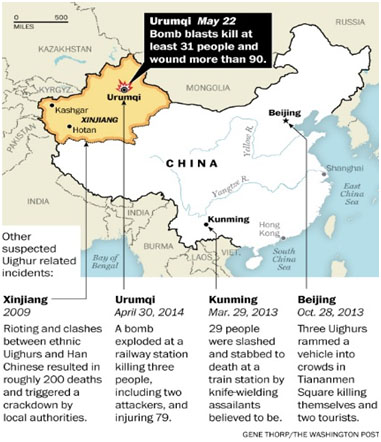

In February, a Uyghur suicide-bomber self-detonated at a hotel in Xinjiang, killing seven. In July 2009, riots in Xinjiang’s capital of Urumqi left 197 dead. This incident received national attention. The provincial government responded by increasing the security budget in 2010 by almost 90 percent, to 2.89 billion yuan ($423 million). The underlying issues of discrimination and economic disparity were not addressed. Consequently, conflicts continue. Last year, 29 people were killed in a mass knife attack at a train station in the southern Chinese city of Kunming. Following the government line, the Chinese media labelled the act terrorism.

The most recent incident comes after the federal government launched an anti-terror campaign last year, following the Urumqi incident, blaming Uyghur separatists and Islamist insurgents seeking to establish an independent state.

China is also cracking down on religious observances of Muslims in Xinjiang. In cities across the region, signs warn people against public prayer. Individuals younger than 18 cannot enter mosques. Video cameras are often trained on mosque entrances by the government to keep track of who comes and goes daily. Civil servants are banned from participating in Friday prayer services and Uyghur college students are not permitted to fast during Ramadan.

Ironically, outside of Xinjiang, Chinese Muslims, mostly ethnic Hui, are not discriminated against by the Han. Some observe it is because they are physically indistinguishable from the Han and Mandarin-speaking. Thus, it seems that the problems in Xinjiang are more closely tied to lack of assimilation of a unique ethnic group, rather than Islamist extremism alone.

Yet, if China continues to threaten Uyghur religious identity, the likelihood of attracting more discontented Muslims to jihadism will grow. Uyghur separatists, to date, seem more inclined to interact with Islamist groups in Pakistan and central Asia for training only, not Islamist indoctrination. Yet, there is a trickle of radicalization in the province, embodied by groups such as the Eastern Turkestan Islamist Movement (ETIM). ETIM’s actual numbers, capabilities and connections to more serious extremists like al-Qaeda or ISIS is unclear.

Strategically located at the border of eight countries: Russia, Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, Mongolia, and the central Asian states of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, Xinjiang can either be a buffer to Islamist extremism or an Islamist foothold into China. As evidenced in other nationalist movements where Muslims are involved, like Chechnya or Bosnia, Islamist foreign fighters sometimes take on a cause whether they are invited or not; or in the case of the Iranian revolution, usurp power once a common goal (overthrowing the Shah) is achieved.

Should Islamist extremists in any of these countries (and there are many) turn their attention east, it would be very easy for foreign fighters to adopt the Uyghur nationalist movement as a Muslim cause and introduce Xinjiang to dreams of an enduring caliphate.

Extremists: Their Words. Their Actions.

Fact:

On May 8, 2019, Taliban insurgents detonated an explosive-laden vehicle and then broke into American NGO Counterpart International’s offices in Kabul. At least seven people were killed and 24 were injured.

Get the latest news on extremism and counter-extremism delivered to your inbox.