Fact:

On May 8, 2019, Taliban insurgents detonated an explosive-laden vehicle and then broke into American NGO Counterpart International’s offices in Kabul. At least seven people were killed and 24 were injured.

Policymakers and the public have rightfully demanded the removal of neo-Nazi, white supremacist, and far-right content from the Internet following the horrific Christchurch, New Zealand mosque murders that were livestreamed on Facebook and subsequently re-uploaded countless times to a variety of Internet platforms.

The tech industry typically demonstrates heightened vigilance following tragedies or scandals involving their services. And greater scrutiny from regulators, media, and advertisers generally spurs the firms to an assortment of short-term actions, including for example the announcement of new policies or restrictions on what type of content can be uploaded.

True to form, following white nationalist Brendan Tarrant’s murderous rampage, Facebook announced it would remove posts offering “praise, support and representation of white nationalism and separatism,” in addition to banning white supremacist groups. As a result, white-nationalist groups—including those that claim to disavow violence such as Generation Identity, Identity Evropa, Les Identitaires, and the League of the South—can no longer operate on Facebook. Other platforms, including Twitter, also suspended accounts belonging to white nationalist groups.

In adopting this policy change, Facebook and other platforms are rejecting self-serving distinctions made by certain far-right groups between so-called ‘violent’ and ‘non-violent’ white nationalists. Before Christchurch, the latter could argue to not be in violation of Facebook’s Terms of Service since they were not explicitly involved in terrorist activity or organized violence. Following Christchurch, Facebook reassessed and expanded its terms to justify removal of content from ‘non-violent’ groups and organizations with well-established links between their rhetoric and propaganda and violence.

In the aftermath of this logical and wholly justified reassessment of its Terms of Service enforcement, Facebook and other platforms should now move forward to ensure the consistent and transparent applications of Terms of Service standards against other types of supposedly non-violent extremist content—namely the type of dangerous ideological material that has inspired generations of Islamist terrorists and murders.

For example, the rhetoric and ideology of Islamist groups like Hizb ut-Tahrir (HT) and the Muslim Brotherhood is unequivocally linked to acts of violence and hate. Yet they are both largely free to operate on Facebook, YouTube, and elsewhere without restrictions.

HT is an international Islamist movement seeking to re-create the Islamic caliphate. HT is banned in at least 13 countries, including the Muslim-majority nations of Indonesia, Bangladesh and Pakistan. HT claims to be non-violent, but its promotional materials have called for violence against Jews and it has been called a “conveyor belt” for terrorists. Its alumni include 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammad and Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the former head of al-Qaeda in Iraq. ISIS fighter Mohammed Emwazi, a.k.a. “Jihadi John,” reportedly attended HT events while in university in England. In early May, CEP researchers identified 11 HT channels on YouTube, and a search for “Hizb ut-Tahrir” yielded 14,300 results. The group also maintains a presence on other major social media platforms with dozens of pages on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, with supporters spreading content using #hizbuttahrir hashtags.

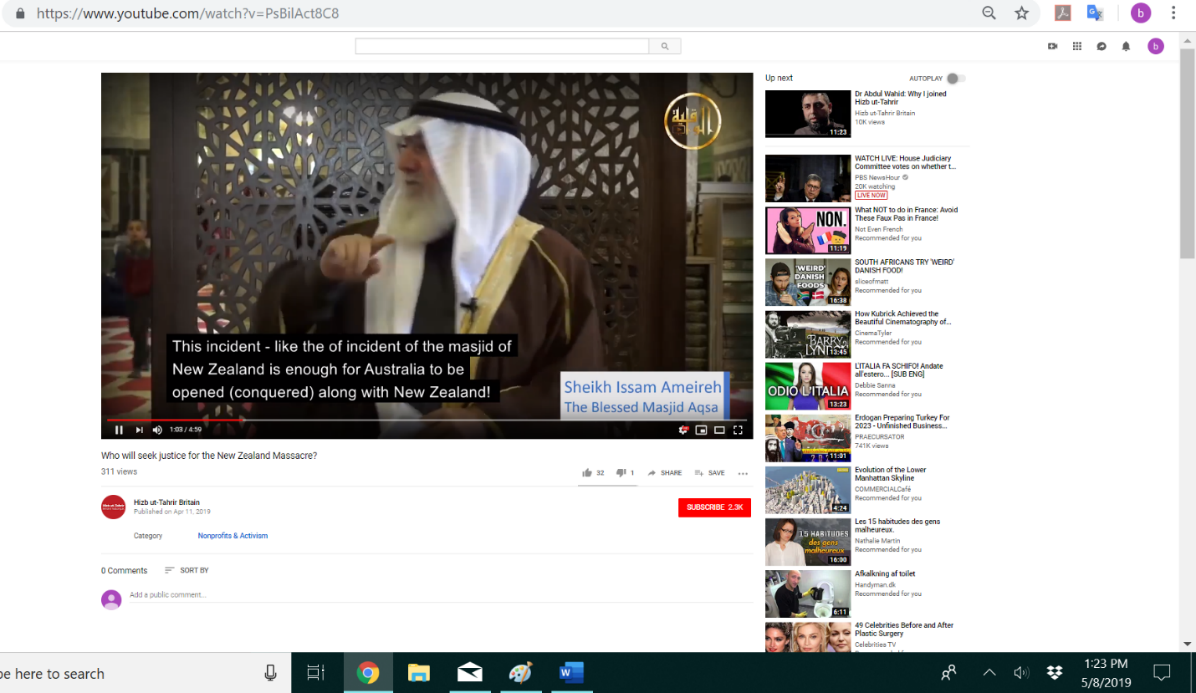

A video entitled, “Who will seek justice for the New Zealand massacre?” on the HT Britain YouTube Page. The video had 311 views on May 8, 2019, and was uploaded on April 11, 2019

The Muslim Brotherhood also claims to be non-violent, even though its actions and ideology reveal the opposite. Al-Qaeda co-founders Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, as well as ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi were all members of the Brotherhood. The internationally designated terror group Hamas, which has engaged in suicide bomb attacks, rocket and mortar attacks, shootings, and kidnappings, is a direct offshoot. CEP researchers identified 19 Muslim Brotherhood and pro-Muslim Brotherhood Facebook pages as well as 12 Twitter accounts in early May. Several of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Twitter accounts are even considered verified accounts by the social media firm.

A video of Yusuf al-Qaradawi speaking at the Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo, Egypt on November 16, 2012. Qaradawi states: “O Allah! Eliminate their (Israel’s) state and remove their rule from the face of your earth and leave them not any path towards your faithful people.” The video had 3,686 views on May 8, 2019 and was uploaded on November 20, 2012.

Tech companies cannot dismiss claims of benign intentions from far-right groups while accepting the same claim from Islamist extremists. Doing so only allows groups like HT and the Brotherhood free reign to spread their hateful propaganda online.

The same must be said about a host of radical Salafist preachers like Yusuf al-Qaradawi, a Muslim Brotherhood leader who has called for attacks on American and Israeli civilians and troops, and the execution of gay people. Similarly, Ali al-Qaradaghi, the secretary-general of the International Union of Muslim Scholars (IUMS), is a vocal supporter of Hamas and the Brotherhood. He is active on multiple social media platforms, including YouTube, Facebook and Twitter, and professes social media plays an important role in the spread of Islam, though “jihad is the greatest way to spread Islam.”

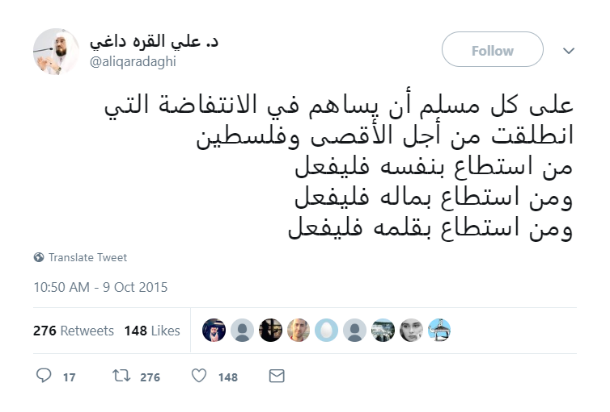

Ali al-Qaradaghi tweet promoting violence against Israel. The tweet had 17 comments, 276 retweets, and 148 likes on May 8, 2019.

Lastly, the alleged mastermind of the coordinated suicide bombings at churches and hotels on Easter Sunday in Sri Lanka, Islamic extremist Moulvi Zahran Hashim, was prolific lecturer for National Tawheed Jamaath who shared his extremist views and explicitly pro-ISIS content on his Facebook pages, one of which had more than 4,000 followers. Sri Lankan Muslim leaders say that beginning in 2016, they raised the issue of Hashim’s extremist posts and sermons to Facebook and YouTube, yet they remained online.

These are just a few examples that highlight the immediate need for consistent enforcement standards across platforms. One form of extremism is no less toxic than another. Tech should not have different standards for different forms of extremism.

Governments in New Zealand, Australia, the U.K., the E.U., and Singapore, tired of tech’s excuses and false promises, are in various stages of passing legislation to regulate and reign-in the industry. Clearly, such regulatory action is needed to hold tech firms accountable for their failures to promptly remove and prevent the upload and dissemination of extremist content.

All forms of extremism threaten public safety and security. What should be demanded of the tech industry must be commensurate with the danger: Clear standards applied universally and enforced relentlessly.

Extremists: Their Words. Their Actions.

Fact:

On May 8, 2019, Taliban insurgents detonated an explosive-laden vehicle and then broke into American NGO Counterpart International’s offices in Kabul. At least seven people were killed and 24 were injured.

Get the latest news on extremism and counter-extremism delivered to your inbox.